MELBOURNE MADE

Church of All Nations, Carlton

Saturday March 19, 2016

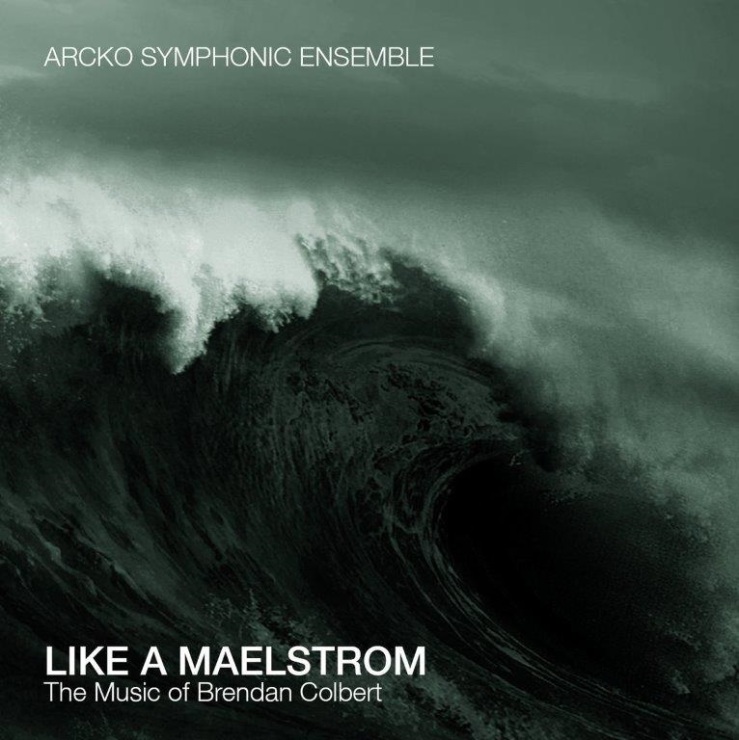

This concert offered a little bit of the old as well as the new – that’s if you could call anything on this program old. Timothy Phillips and his symphonic ensemble specialize in challenging new music and yesterday had that in spades with the world premiere of Tim Dargaville‘s Kolam, a return visit to Caerwen Martin‘s X-Ray Baby (featured on the first Arcko CD), Ingressa of 2009 by Elliott Gyger, and Brendan Colbert‘s . . . like a Maelstrom which is the title of the latest CD from these players, launched at this concert.

It’s been quite a few years (twenty?) since I last visited this church which has now become a community powerhouse – and it shows. The interior last night had a few pews along the side walls while the central space was lined with individual, if not very comfortable, chairs. The Arcko players worked from the front facade where the preacher’s gallery sits, on the same level as the audience which meant that, to see individuals at work, you had to crane; which the lady in front of me did throughout the evening, although she seemed indiscriminate in her viewing choices, contorting her body in the direction of players who were, at the time, static.

Still, she could do little to disrupt Tim Dargaville’s new work, taking its impetus from a Tamil religious practice. The composer is making no attempt to absorb and discharge Indian musical influences: no Bollywood echoes, no resuscitated Ravi Shankar. The recurring motif is a falling major 2nd, an upward leap of a 5th, then back to the original interval. But for much of its length, the score is of interest for its textures; there is a melody for cello that eventually emerges, followed by another for horn, but one of the distinctive points of interest is a brisk section for winds alone prior to a fulminating climax. As an example of management of forces, Kolam makes a positive impression but its philosophical underpinning remains a mystery to this listener, even if the work’s format presents few problems.

Gyger’s work is based on a type of religious chant that emanates from the town of Benevento, a Campanian city near Naples. Scored for wind and string quintets, piano, harp and two percussionists, this work is based on an entrance chant for Easter Sunday, a dialogue between Mary Magdalene and the angel at Christ’s tomb. Using far more notes for a musical phrase than the more common Gregorian, this sample of Beneventan chant is angular, inclined to more abrupt intervallic leaps than you’d expect, and not averse to ending phrases mid-word. You would need a score to trace the melody’s use in this piece, as the instrumental output is strikingly dense, but its climactic point, an Alleluia divided between strings, solo horn and tubular bells, is effectively jubilant, bringing to mind the more restrained outpouring in the final Taize-illustrating movement of the Laudes octet by Nigel Butterley, on whose music Gyger is an authority. Still, throughout this work’s progress, the percussionists have all the running, Amy Valent-Curtis and Peter Neville dominating the action with a wide-ranging battery of sound-sources.

Martin’s construct aims to suggest hospital sounds, beginning with rustlings and subdued suggestive wisps, eventually graduating to a very forceful climax. Dedicated to the composer’s two daughters, the score has graphic elements based on her children’s scans and X-rays; like Gyger’s chant, constituents you can not easily assimilate from what you hear. Given that the composer has clearly spent a good amount of time in medical institutions, her work succeeds in suggesting the mechanics of the hospital experience. Well, you can pick out passages that strike you as suggestive; I heard sirens, nurse-doctor confrontations, the lapping of amniotic fluid, a loud labour, disputes in emergency. Once the thesis is suggested, you can hear whatever you want to – or fear. Despite Martin’s description of X-Ray Baby as abstract by nature, it takes very little effort to find musical illustrations of medical realities.

Colbert’s score owes its title to an Emily Dickinson poem of morbid imagery, even for that death-haunted poet. It is a double concerto for trumpet and piano with emphasis on the latter which is not silent throughout the work’s half-hour length. This was a remarkable tour de force from Peter Dumsday; getting the notes under his fingers an achievement in itself but maintaining stamina across an unforgivingly active part was a tribute to the performer and, on his part, to the composer. By comparison, Bruno Siketa‘s trumpet had things easy, not entering for some time, then kept restrained by being muted for the concerto’s outer segments. Once again, percussion played a major role and the chamber orchestra strings, bowing away fiercely in the first five minutes, stayed close to inaudible for a good part of the action. To his credit, Colbert does not compromise, maintaining tension without much relief, the default expression marking being a determined forte, it seems. At certain moments, the experience brought back memories of Cage’s 1958 Concert for Piano and Orchestra; not in its soundscape, because Colbert’s is through-composed, not left up to the musicians to choose their own paths, but for the massive onslaught of sound that coloured so much of its impact.

It’s an uncompromising voice, both enervating and exciting to hear in an age when contemporary composition is finding it difficult to sustain interest, let alone an audience. In that regard, . . . like a Malestrom represents the sort of initiative for which the Arcko organization exists. Whether or not it offers pleasure is irrelevant; what it does give you without holding anything back is a horizon-expanding experience, one where your ears are challenged to an aesthetic confrontation. At a new music concert, I can’t imagine anything better.