DVORAK’S SERENADE

Concert Hall, Queensland Performing Arts Centre

Monday August 7, 2023

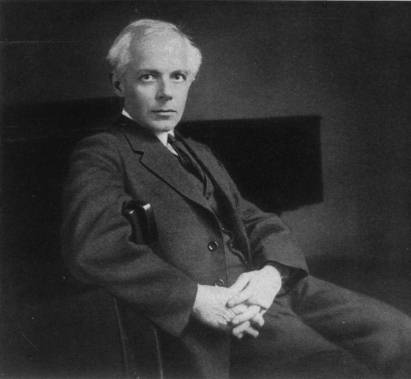

Bela Bartok

Fourth in an eleven-concert series, this Brisbane appearance by the ACO under Richard Tognetti‘s artistic and concertmasterly leadership divided neatly into opposing halves. Before interval, patrons were offered a fairly contemporary opening with Caroline Shaw’s Entr’acte of 2011, a piece that the American composer wrote while a student at Princeton. This was followed by Tognetti’s new arrangement of the 1934 Bartok String Quartet No. 5, called ‘in B flat Major’ because it starts and ends in that key (roughly). After interval, we moved back in time a tad for Josef Suk’s Meditation on the Old Czech Chorale ‘St Wenceslas’, composed near the outbreak of World War One and used as a musical act of resistance against the German invaders (following in Sibelius’ anti-Russian footsteps). And we concluded with the night’s title, Dvorak’s delectable Serenade for Strings of 1875.

This last is a string orchestra staple but the ACO hasn’t recorded it, as far as I can tell. So what? There’s an awful lot of music for the same forces that the group has not dealt with, but the current personnel could make an impressive interpretation, worth setting down on something more public than the organization’s own tapes. Tognetti encouraged his players to give full vent to the composer’s throbbing expressiveness while keeping the lines clear. Not that clarity in this Romantic product would be a problem with this group where the bass lines feature three cellos and one bass only.

Once again, the two violin contingents made an impressive display, the seconds immediately with a finely shaped outline of the first movement’s opening subject, even more telling on its restatement at bar 13. In fact, the entirety of this Moderato demonstrated great care in preparation, from the soft high chords that concluded bars 22 and 24 to the modestly projected cello lines from bar 66 to near the movement’s end. But then, we’re treated here to one of Dvorak’s most tender lyrics, even quite early in his prodigious output.

The mellifluousness continued in the Valse/Trio with some danger spots deftly achieved, like the strings’ octave doubling from bar 11 on, which many another body plays with bursts of suspect intonation, and the delectable skipping exhibition for second violins and cellos at bar 37 which impressed by its grace and positivity. I admired the pace of the following Scherzo and a uniformity of address that typifies this body, particularly while they worked through the thick-and-fast canonic entries that dominate this movement’s progress. Even the lack of bass heft wasn’t too obvious at the bar 42 fortissimo-for-everyone tutti where cellos and bass have the running. And the ensemble created a finely-spun melancholy moment at the bar 286 a tempo as the melodic material is decelerated and subjected to a placid musing before the concluding rush.

You would be hard pressed to find a more appealing version of the ensuing Larghetto – from the delicate but disciplined opening, straight into the business, to the lightly tripping Un poco piu mosso beginning at bar 47 with not a double- or triple-stop unachieved briskly. Even the note-spinning high violin line that dominates proceedings from bar 54 to bar 63 (an odd creative lapse in this eloquent essay) exercised interest for the piercing thinness of its contour. While you could understand the need for tempo relaxation in the vivace last movement, I’ve never understood why everyone slows down for the episode beginning at bar 85. Is it viewed as the beginning of a new ‘step’, perhaps? At all events, we were caught up in the rapid scurrying of this allegro‘s central pages before the melting-moment return of the work’s opening theme at bar 344, and the brusque furiant that here brought us home to generous popular approval. Just as you’d expect from this outstanding body that is blessed with consistency of personnel.

Not much to report about Entr’acte which moves between rather ordinary chord groupings to some special effects harking back to the 1960s. The only thing I gained from this performance was an appreciation of the work’s variety of timbres – which are not apparent from available recorded versions. Or perhaps American orchestras aren’t fussed about these details which, as far as I can tell, are the work’s main interest . . . alongside the concluding cello solo, carried off here by Timo-Veikko Valve with a kind of phlegmatic consideration.

Similarly, not much remains in the memory of Suk’s brief hymn treatment. The opening pages are lushly scored although the harmonic vocabulary stays in A natural minor for the entire first part of 39 bars – not an accidental in sight. Double bass Maxime Bibeau was put to a difficult task, having to negotiate a part that called for three players, most obviously in the moving (and exposed) A Major triads of the last three bars. But the work was handled with considerable attention to its inbuilt surging character, based as it is on a kind of dour Gregorian chant and not the wider-ranging compass of the Tallis Fantasia with which Suk’s work bears slight comparison.

For my money, the night’s interest came with the Bartok arrangement. After a few days, I’m still doubtful about the point of this exercise, apart from giving the ACO an addition to its repertoire. From the opening avalanche of B flats, it was clear that we were in a new country where individual voices were subsumed in a kind of musical groupthink. Voices impressed as powerful blocks but some polish came off the details, like the trills in bars 21 to 23 of the opening Allegro. Not that this impression was uninterrupted, as in the second subject’s arrival in bar 44 which preserved its striking sinuosity, and the orchestral texture was pared back every so often, yet those unison/octave recurrences dominated the movement’s progress as at bars 59, 126 (minor 2nds, for a change), 159, and 210 – all of which served as anchors in a welter of thick part-writing; difficult to imbibe even in the original.

I seem to remember that the Adagio began with single instruments, the full corps entering at bar 10. Again, here significant details sounded blurred, like the five-note semi-chromatic rapid runs that begin at bar 26 but which lacked the original’s crepuscular mild stridulatory suggestiveness. It was a relief to get back to the slow-moving isolated trills after bar 50’s Piu andante.

Of the work’s five movements, the middle Alla bulgarese emerged best in this string orchestra garb, notably at the burst into a C Major/minor/modal three-bar break at bar 30: one of Bartok’s more folksy surprises. As well, the 3+2+2+3/8 Trio showed the ACO’s expertise in dealing with irregular rhythms; but then, the group’s had plenty of practice, ever since the group played the Sandor Veress Transylvanian Dances nearly 30 years ago. Even so, this Bartok is much more demanding. The composer’s counterpoint is less interwoven in these pages, even if the parallel and contrary motion passages are persistent, particularly in the Trio‘s later stages; so the employment of massed (and supple) strings doesn’t interfere with your enjoyment of this dance.

The outer stretches of the Andante maintained their shadowy atmosphere well enough, if the hard-worked Piu mosso from bar 64 to bar 80 proved wearying with the viola/cello/bass work opaque, if not muddy. Still, that made the following 10 bars of tonally inflected Tranquillo very striking for its purity, exercising a kind of static eloquence. Then, the vivace final movement proved an exercise in stamina, exemplified by an initial attack that was as ferocious as any I’ve heard from a quartet versed in this work. Of course, it had its inbuilt slackings-off and accelerations but the ensemble’s enthusiasm and responsiveness went a fair way to making a positive impression in the rapid-fire presto pages.

Even so, the quartet’s finale raised similar questions to those from the first movement. Has the transference achieved much beyond an emphasis on aggression? Is the exchange of intimacy for amplitude worth the transformation? Even with gifted trios of violas and cellos, is the sacrifice of individual lower voices compensated for by laudable collegiality of articulation? This is not the first of the ACO’s transliterations from quartet to chamber orchestra format but it is a questionable one, chiefly because so much goes on in the original that becomes either muffled or muted in the transference. For all that, the performance enjoyed a hearty welcome from last Monday’s audience here – which shows that – once again – I’m in the minority.