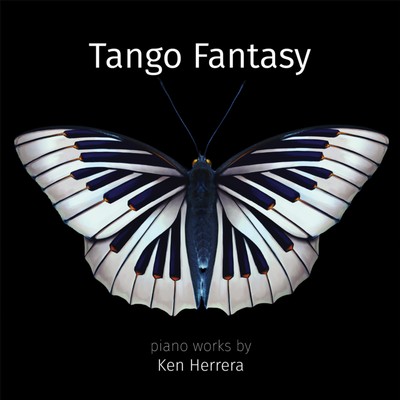

TANGO FANTASY

Move Records MCD 649

The composer/pianist presents four of his works on this disc: two short isolated pieces, and a pair of collections, finishing with the five-movement, 33-minute-long Tango Fantasy. Herrera studied piano at the Tasmanian Conservatorium of Music, then moved into composition. He appears to be self-taught in this latter field and – unfortunately – it shows. You’re not getting many contemporary sounds here; Herrera is content to manipulate a harmonic vocabulary of rudimentary proportions and his professed devotion to the tango is not persuasive when it comes to putting that particular dance into his own language,

For instance, the opening Tango Waltz begins with some flourishes that might suggest a tango but, 30 seconds in, the piece has settled into a 3/4 rhythm. Following this straightforward move to waltz-time, Herrera doesn’t move out of it. Furthermore, the melodic content is rather wayward; sure, there are repetitions of his basic tune, punctuated by episodes that have little relation to anything but themselves. Apart from a well-pedalled scale eruption about two-thirds of the way through, there’s not much here to raise expectations of virtuosity; some flourishes are welcome but the 2018 piece is couched in a pre-Nino Rota/Fellini atmospheric without the original’s spartan melancholy.

Pairing up with this waltz is the album’s other brevity, Herrera’s Third Nocturne from 2012 which aims to suggest a Latin American night spot complete with its atmosphere-establishing piano in a blending of bossa nova and blues. Well, you get the first-mentioned’s rhythm, all right – it obtains throughout – but the blues consists of some predictable chords and not much besides. Our nocturne isn’t in the Field/Chopin line but more along the lines of something you might hear at a cocktail bar; sadly, not one where you’re tempted to tip the pianist. As with the waltz, the piece sounds aimless in its right hand which wanders at its own sweet will in a chain of 7th chords and tinklings.

Herrera’s first major construct is a Suite dating from 2013. The inspiration comes from Bach – a laudable aspiration, although the shape of the collection puts it closer to Grieg’s Holberg or even the Karelia of Sibelius although its four elements are given non-suggestive tempo titles: Allegro, Allegro, Andantino, Presto. The first is proposed as an introductory toccata but the only shadow of that form comes close to the end in a quasi-improvisatory passage that recalls some of the foibles of Sweelinck. For the most part, it proceeds like a fitful study with left-hand cross-overs for excitement, building to a loud highpoint rather early in proceedings but, like a Buxtehude toccata,. owning several sections.

At the end of this opening, you’re also left with several questions about the movement’s harmonic shape which tends to follow a predictable path, if sometimes an ungainly one because it veers off from its own patterns more than little self-consciously. We’re in much more solid Bach territory with the second Allegro which begins like one of the Inventions but lacks the rigour to follow a simple contrapuntal matrix, the left-hand settling into a bass role where you expected a mirroring of the initial statement. Progress is sometimes quirky, but not in an adventurous way – for instance, a sequential pattern is held up for a moment when a repetition is interpolated so that you’re left feeling unbalanced when the sequence is resumed. Later, when the left hand gets hold of the initial line, the treble provides a functional harmonic accompaniment rather than a complement. At about the 1’30” point, we enter a new world of repeated chords for a moment, returning almost instantly to the suggested/unrealized linear interplay of the opening.

Herrera sees this as a lively dance movement; to me, it’s more in the nature of a march in that I can’t see any potential choreography beyond a military stamp. When it comes to the obligatory slow movement, we are offered an Andantino that opens with a simple old-fashioned melody, followed by a series of episodes that numb with their predictability in terms of shape and modulations. Added to which, the composer reaches some points where inspiration is at a premium and we experience a good deal of repetition and note-spinning, e.g. at about the 3′ 50″ mark and at 5′ 00″. An abruptly determined conclusion sits at odds with the placid opening; it’s as though the writer has turned semi-aggressive and avoided a tempering of his mood.

When we reach the Presto, Herrera points to the gigue conclusions to Bach keyboard suites and proposes a further historical reach by wanting to summon up the Irish jig spirit as well. He opens bravely, with a flourish that hints at Litolff’s Concerto Symphonique No. 4 Scherzo before we reach a melody peppered with hemiolas. Before long, the jig has turned into a momentary waltz, then coming back to jig with some slight suggestions of a blues chord or two. A descent to the bass register moves us back into the land of the totally expectable, followed by a rise in alt – and we’re back to Litolff, albeit rather laboured. A chromatic rise brings us to a reprise of the opening material, and a soft-dynamic ending with preparatory booming bass and ornamental sextuplets on top.

This is the most effective of the suite’s movements, mainly because of its energy and occasional charm, yet it still leaves an impression of beating the bounds through interludes – to the point where the exercise sounds like a disjunct rondo.

But there’s more. Herrera’s final offering is the 2016 Tango Fantasy in five movements that begins with a solid Andante – Allegro – Allegretto – Presto sequence. The opening is a sort of recitative, beginning with a single line that acquires another as well as some gruff bass burps before reaching for some chord chains that would have satisfied more if the composer had been more severely self-critical, giving coherence to his modulations and animating the piece by using his instrument’s outer reaches with some purpose.

The remaining three sections are all tangos, taken at various speeds, the fourth being something of a recapitulation of the second although the pace doesn’t justify the Presto label. I found it difficult to detect how the Allegretto was related to anything else, although it opened in a quasi-improvisatory manner that suggested the piece’s first pages/bars. But a great deal of territory is covered by the fantasy nomenclature, so – as with Chopin and Schumann – you just have to go with the prevailing flow. We now come to a Vals – Allegro vivo which follows a similar Rota-type insouciance as we heard in the opening Tango Waltz; the main tune opens deftly enough but fails to live up to its promise with a rather aimless consequent to its initial statement. Here the intention is clearly to spike up the piece’s orthodox harmonic scheme with some wrong-note interpolations. That might have come off if the overwhelming tenor of the movement was not so traditional at its many harmonic fulcrum points. Added to this, some of the movement’ phrases didn’t balance; and you’d be working hard to find much vivo in these pages.

Now attention turns to the Milonga, the tango’s precursor; this movement is also set up as a Presto, which it isn’t. Here is a harmonically orthodox dance with some traces of the habanera’s triplets and at least four passages of fortissimo writing that come straight from the Lisztian handbook of virtuosity if not as dynamically sustained or as digitally taxing as in the Hungarian master’s workplace. An Andantino opens questioningly but follows an inchoate path, taking its time before settling into a languorous tango, then seeming to doodle a melodic path leading in no particular direction. In fact, this whole movement struck me as aimless if centred on a minor tonality (G?) – as is so much of the music on this CD – before a concluding over-emphasized tierce de Picardie.

at the start of the concluding Presto, Herrera introduces a key motif of five consecutive semiquavers rattled out like automatic fire before moving into a Piazzolla-reminiscent melody that gives a format to this rondo-tango which comes equipped with a substantial coda. Again, I’d question the tempo direction which, to my ear, sounds in actuality more like a tempo di marcia. But the real problem comes not from the piece’s impetus, which is well-sustained, but from the diffuse nature of its harmonic ramblings which lead into some thorny thickets before moving back into diatonic safety.

Nothing wrong with being a tango tragic. Never forget that splendid man-of-letters Clive James and his installation of a special room in which he could practise this specific dance: that’s enthusiasm. But, for a composer, you have to add something original to a field that boasts the riches of Albeniz in D, Por una cabeza, La Cumparsita, Besame mucho, and even Libertango. This CD is the work of a talent that appears devoted to this specific form but his output needs more focus, not to mention more sophistication.