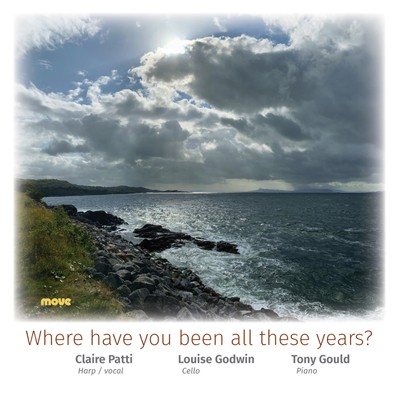

WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN ALL THESE YEARS?

Claire Patti, Louise Godwin, Tony Gould

Move Records MD 3469

There’s something disarming about this album which is a collection of songs/folk-songs – several of them well-known – performed as trios, duets and solos by Claire Patti (harpist and singer), Louise Godwin (cellist but not employed as much as she could have been), and Tony Gould (pianist and the heaviest participant in this amiable exercise). I say ‘well-known’, but that might only apply to that generation that boasts Gould and me (he is my senior by a few years). The Skye Boat Song, My love is like a red red rose, Londonderry Air, The Last Rose of Summer, Black is the colour of my true love’s hair and Molly Malone were standard articles of faith in my youth and all enjoy a re-working here.

As well, you will come across a few that ring bells in the memory, if not very clamorous ones: Carrickfergus, Strawberry Lane and Ae fond kiss. Gould and Co. have included an Irish lyric that I’ve never come across – Tha M’aigne fo ghuraim (This gloom upon my soul) – and an English traditional song that none of those great 19th-into-20th century collectors seems to have bothered with: Sweet Lemany. Not to mention a Scottish tune that sounds more promising than its reality in She’s sweetest when she’s naked. Then there’s Idas farval (Ida’s farewell), written by Swedish musician Ale Carr, and Jag vet en dejlig rosa (I know a rose so lovely) which is a traditional tune, also from Sweden; I suspect that both of these spring from Godwin’s interest in that Scandinavian country’s music. From left field comes A little bit of Warlock, which sets some pages from the Capriol Suite, namely the Pieds-en-l’air movement.

The ensemble beginsn with Sweet Lemany, which may have origins in Cornwall, Ireland, or Suffolk; it has certain traits that argue for an Irish genesis. But the setting is original,, first in in that Godwin maintains a one-note pedal throughout, pizzicato and keeping to a mobile rhythmic pattern. Patti sings with a light, refreshing timbre while Gould informs the piece with subtle inflections and brief comments/echoes. For all that, Patti sings four of the five verses available in most editions.

Gould takes the solo spot for William Ross’ Skye Boat Song and, apart from a winsome introduction, sticks to the well-known tune right up to the final bars where the straight melody is subsumed in a brief variant. Most interest here comes from following the executant’s chord sequences which follow an unexceptionable path throughout a mildly meandering interpretation. Gould gives brief prelude to My love is like a red red rose before Patti sings the first two stanzas. Godwin offers a cello statement, before the singer returns with the final two stanzas and an unexpectedly open concluding bar. Gould occasionally offers a high trill to complement Patti’s pure line. And the only complaint I have about the vocal line is the singer’s odd habit of taking a breath after the first few syllables of the third line in most of the stanzas.

Carr’s sweet if repetitive lyric is a sort of waltz with three-bar sentences/phrases, in this case giving the melody first to the cello, then the harp, before the cello takes back the running. The piece’s form is simple ternary and we certainly are familiar with the melody’s shape before the end. More irregularity comes in the Swedish traditional song from the 16th century with its five-line stanzas, here handled as a kind of elderly cabaret number by Patti and Gould, whose support is a supple delight beneath Patti’s somewhat sultry account of what textually should be a love song but musically sounds like a plaint.

The Warlock movement, here a piano solo, gets off to a false start and Gould can be heard saying that he’ll start again. For the most part he is content to follow the (original?) Arbeau melody line and reinforce the British arranger’s harmonization with some slightly adventurous detours along the path. A variant appears shortly before the end but the executant eventually settles back into the format and plays the final two Much slower bars with more delicacy than the original contains. Patti sings two stanzas of the three that make up the ‘standard’ version of Carrickfergus and invests the song with an infectious clarity of timbre, especially at the opening to the fifth line in each division with Gould oscillating between the unobtrusive and mimicking the singer when she moves into a high tessitura.

A harp/cello duet treats James Oswald’s She’s sweetest when she’s naked, which has been described as an Irish minuet (whatever that is). The only peculiarity comes with a change of accent to slight syncopation, first seen in bars 3 and 5 of the first strophe. Patti plays the tune through twice, then Godwin takes the lead for another run-through. Some laid-back ambling from Gould prefaces the Danny Boy reading for solo piano, with just a trace of Something’s Gotta Give before we hit the melody itself. The pianist does not cease from exploration and offers some detours to the original line, as well as a couple of sudden modulations to restatements in a refreshed harmonic setting. For all that, the Air remains perceptible across this investigation, the CD’s longest track.

Staying in Ireland, Gould gives an alluring prelude to The Last Rose of Summer before Patti starts singing Moore’s lines. Godwin has a turn at outlining the original Aisling an Oigfhear melody before the singer returns with the second stanza, then omitting the third, with Gould providing a postlude that puts the first phrase in an unexpected harmonic context. As with all the vocal items on offer, this is quiet and unobtrusive, some worlds away from the habitual thrusting treatment demonstrated by generations of Irish tenors bursting into the role of Flotow’s Lyonel.

Across the sea to Scotland’s Black is the colour of my true love’s hair which Gould opens through some sepulchral bass notes before giving the melody unadorned and unaccompanied before moving into a fantasia that harks back to its source material before resolving into another re-statement of the melody and a reappearance of the opening’s repeated tattoo. This version is comparable in colour to some of the more conscientious American folksingers who have recorded versions of this work, making a slightly unsettling celebration of what is a love-song in a minor key (mode!?) context.

Back across the sea to the island, Godwin plays Tha M’aigne fo ghuraim as a solo, punctuated by sudden turns and grace notes; at well under two minutes, the CD’ shortest track but probably its most obvious and characteristic in terms of its country of origin. Another piano solo, Gould gives us a preamble before playing Strawberry Lane through straight once, then almost doing the same thing again before following his pleasure at the end of the second stanza. Of course, he returns to the melody en plein air near the end but concludes with a reminiscence of his earlier elaboration and an unsatisfying tierce to finish.

Another Burns lyric, if a despondent one, in Ae fond kiss brings Patti’s calm delivery into play once again. She sings all the stanzas except No. 2 in the set of six. Gould offers a mid-flow interlude which, I suppose stands in for the missing lines but the song’s delivery suggests a rather odd 3/4 rhythm as opposed to the more bouncy original 6/8. But the executants’ restraint is put to happy employment throughout. Molly Malone brings up the rear and is another piano solo where Gould plays the stanzas’ sextet several times, giving less space to the three chorus lines. It’s plain sailing through this very familiar melody, the pianist content to follow the air’s contour.

Not everything on this diverting disc works ideally. Some of Gould’s chords sound like abrupt breaks in an otherwise placid flow, some notes don’t sound, and Godwin’s cello seems uncomfortable on one track. Still, you’ll find plenty of material here to entertain and over which you can reminisce – which is clearly (for me, at least) the whole point of the exercise.