BRAHMS & STRAUSS

Australian National Academy of Music

Melbourne Digital Concert Hall

Concert Hall, Queensland Performing Arts Centre

Friday September 11, 2020

BRAHMS & STRAUSS

Australian National Academy of Music

Melbourne Digital Concert Hall

Concert Hall, Queensland Performing Arts Centre

Friday September 11, 2020

FANTASY

BOHEMIAN SPIRIT

Lachlan Bramble, Ewen Bramble & Anna Goldsworthy

Melbourne Digital Concert Hall

Thursday August 27, 2020

‘Schaupp has been a stalwart of this country’s guitar world for close to 40 years: in her own right as a soloist, as a concerto performer with state orchestras, and as a collaborator with musicians like Umberto Clerici and the Flinders Quartet. On Saturday evening, she presented this no-frills recital from her home with nobody else but a recording technician in the room with her. Great to see that Musica Viva has embraced the new model of mounting spartan events: one performer providing her own space and not playing too much in case of mental overload in a time of musical famine.

Schaupp’s choice of diet spanned a wide time range, opening with a brace of Scarlatti sonatas and taking in some modern classics of the guitar repertoire, with a side-step to Australian composer Richard Charlton’s Suspended in a Sunbeam, written for this performer last year. Of course, some of these pieces have become familiar from the artist’s CDs: Scarlatti’s Keyboard Sonata K. 208 (L. 238), Brahms’ Wiegenlied and Llobet’s El Noy de la Mare (the lullabies), Una Limosna por el Amor de Dios by Barrios, and Leo Brouwer’s Elogio de la Danza. These date from at least a decade ago in Schaupp’s recording career; apart from the freshly-minted Charlton piece, the program’s other unrecorded works came as no surprise: the BWV 1000 Fugue in A minor for lute by Bach, and an extra Scarlatti sonata, K 322 (L. 483), which was more successful as a guitar transcription than the other sonata by this composer performed here.

After a Musica Viva-lauding address by a ‘suit’ whom I didn’t recognize, being distracted by negotiating volume and access to scores, Schaupp began operations with one of those remembrances or salutes to indigenous land rights – a gesture that has quickly become a behavioural cliché which could even be well-intentioned but which never fails to annoy because of its tokenism. Remember those sad white people in Clifton Hill who put plaques on their houses noting that their lots really belonged to the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung, only to have some Aboriginal people knocking on doors and laying claim to those boastful houses? They were invited in for cups of tea, which says all you need to know about the depth of such acknowledgements.

Both the Scarlatti works were arranged by Schaupp herself and the ‘Adagio e cantabile‘ K. 208 made for an amiable opening with both repeats observed. My only quibble was the avoiding of the 5-note chord that ends bar 13; well, not so much an avoiding but an impossibility, given the instrument’s low operating level at that point. The faster K. 322 is better-known among keyboard players and is gifted with one of those trademark Scarlatti passages of courtly play from bar 36 to the half-way point, and again from bar 73 to the end; the harmonic transparency at these points came over with particularly gratifying clarity in Schaupp’s interpretation

Are you uncertain about the provenance of Bach’s works for lute? Join the club. Before the Early Music Brigade got under way, Segovia cruelled the authenticists’ pitch by transposing, transcribing and transliterating a good deal of Bach’s music. He didn’t leave Scarlatti untouched either, making a popularly-used guitar version of the L. 483, the second of Schaupp’s offerings.

The G minor Fugue, well-known in a violin version, is taken up a tone by most guitarists, I believe; Bach might have moved it himself, for all I know. Schaupp played a pretty clean reading with some passing glitches in bars 44 and 47 but with an otherwise sustained accuracy, reaching a well-prepared climactic point at bar 59 and onward, then realising the smothered tension of the suspensions in bars 93 and 94 before the sudden near-cadenza in the penultimate measure. Here was a measured interpretation without imposed theatrics or a resonance-besotted bass line; rather, the lines were delivered with balance and dynamic control.

Schaupp’s husband, Giac Giacomantonio, arranged the Brahms piece for her and expanded the song to three verses. No surprises here, even if the piano accompaniment’s slight syncopations did not appear to survive the move. With the arrival of its companion piece by Llobet, we entered the realm of straight guitar music, this work and what followed all original compositions. Not that there is much more to the Spanish composer’s Catalan folk-song arrangement than there is to the Brahms lied: one page divided into two halves, one work in 6/8 and the other in 3/4, both placid in emotion (as you’d expect). It was hard to determine why Schaupp seemed so anxious to get off the final D of bar 6, or why the lower notes of the thirds that end bar 5 didn’t resonate. But then, I didn’t register whether or not they appeared at the bar 7 repetition. A simple piece, but a pleasure to come across something which takes into account the instrument’s potential for colour and chord spacing.

With Brouwer’s two-movement Elogio, Schaupp jumped into a contemporary stream; even though the work dates from 1964, the Cuban composer speaks an adventurous language which takes dissonances in its stride. at odd points verging on twelve-tone writing although pedal points and the first movement’s Major 7th characteristic argues for a tendency towards a tonal centre. The executant employed plenty of rubato in the opening Lento, which is a kind of tribute to dance in its juxtaposed flashes of motion and near-stasis, the whole comprising a mobile core surrounded by pairs of ten bars showing relative quiescence.

Brouwer’s second movement obstinato deals, like the first, in gruppetti, but here much more aggressively. The entire movement hurtles forward, notably in the central Vivace in 2/4 which reaches a climax in a vehement repeated rasgueado chord before returning to the rapid, metre-changing material that began the movement, followed by a vivace coda. Schaupp displayed an excellent command of this demanding work, at ease with its many jumps in emotional and technical content, building an impressive structure in each movement while showing no hesitation in vaulting between Brouwer’s juxtapositions of the frenetic with one-line meditation.

Charlton’s work takes its inspiration from a 1994 Carl Sagan speech about the Earth and its position in the cosmos. The Australian composer subtitles his piece Thoughts on the ‘Pale Blue Dot, as photographed by Voyager 1, and he interpolates in the music a text of his own composition with two brief Sagan excerpts. Charlton gives his performer (guitarist and speaker in one, preferably, as here) leeway to pronounce the words over pauses or repeated patterns; Schaupp, the work’s dedicatee and commissioner, showed a reassuring ease with the score. A good deal of its progress is spasmodic, the accompaniment to the text tersely episodic but hard to take in because the words get in the way. Charlton inserts two passages where the speaking stops and the musical content presents as more sequential and lyrical. You come across some moving passages, as when the composer returns to lyricism after the speaker comments on the ‘cosmic dark’ of our universe, and at the work’s end where the last chords present an affirmation of our small-scale existence on the rim of infinity.

Barrios’ tremolo study seems to be a rite of passage for every aspiring guitarist but it has an underlying sweetness of melody that complements the middle fingers’ exercise work. I liked Schaupp’s interpretation which gave a necessary stress to the middle-range arpeggios – the tune, if you like – rather than belting out the bass dotted minims that open nearly every bar, or over-emphasizing the efficiency of her top tremolo. Mind you, she had given us her view of the work in a prefatory talk, finding a ‘prayer’ in this music. Which may well be the case, if only for the consolatory turn to E Major at bar 56 and he ‘Amen’ coda at bar 72. Certainly, it brought this brief recital to a satisfying conclusion: rounding out a trip from the firm benediction of a brilliantly constructed fugue to the touching vision of an old woman asking for alms – all too relevant a backdrop to this year of disasters.

LISZT’S ITALIAN PILGRIMAGE

Move Records MCD 593

It only seems like last week that I heard this young Melbourne pianist working his way through Liszt’s Deux légendes. In fact, it was almost the end of March and Lee was appearing as the second recital-giver in that excellent and timely innovation, the Melbourne Digital Concert Hall, during which he gave us his reading of those picturesque sacred tales with lashings of sonorous fabric. Not much has changed, it would seem, since this CD’s release last year but the performance is masterful, carrying you past a good deal of heaven-storming piety and grandiose musical vistas.

The first of these, St. François d’Assisse: La prédication aux oiseaux, enjoys a reading that is exemplary in its detail, most obviously when the birds are involved before and after the saint starts his avian address. Lee keeps his texture clear despite observing pretty much all the ‘accepted’ pedal markings; even when the grouping gets a touch cluttered, as in bars 42 to 45 where the twitterings reach their peak, the pianist keeps the demi-semiquaver patterns lucid..

Further, once the saint starts preaching in earnest and the birds settle into a state of quiescence from bar 68 onwards where the chords gain in majesty, the interpretation gave an earnest, urgent outline of the music’s intended move towards the preacher’s plunge into ecstasy and the high-flown climactic fortissimo points in A flat and B flat. The composer’s moving transition from the end of Francis’ address back to the birds’ return to their natural state (changed, one hopes, by the experience) also brought about a sense of completion; you may not believe in the event but the musical depiction gives a remarkable depiction of this legend, all the better here for Lee’s responsive performance.

More excitement prevails in the second legend, St. François de Paule marchant sur les flots. The piece is a near monomaniacal treatment of the opening three-octave theme on which the composer whips up a stormy Strait of Messina crossing that reaches its apotheosis at bar 103. Again, Lee keeps his textures free from over-blurring, especially in the most active passage which is not so much thematic as fiercely aquatic – bars 72 to 98 – with chains of alternating chords, double-octaves and runs of chromatic thirds. The pace is not startlingly fast with attention-grabbing acrobatic leaps to summon up the blood, but the accelerandi and stringendi come across as moderate, serving to underpin the miracle being depicted. Even at the end, where Liszt opts for an affirmative-action ending rather than leaving the saint to enter Sicily in an atmosphere of pious and reserved thanksgiving as you might have anticipated from the Lento at bar 138/9, Lee keeps the triumph leashed.

These two pieces come at the end of the CD; not positioned as reassurances of Lee’s talents but well-tailored to amply display his gifts, not least one for investing both works with gravitas, the realization that we are listening to music that can stand on its own feet when treated with dedication. This pianist is conscientious in his approach which gains a great deal from technical security but just as much from a level-headed view of Liszt’s picture-painting.

This CD’s main content is the middle volume of the Années de pèlerinage – the one specified as having Italy as its inspiration. Liszt compressed his experiences into seven pieces: three to do with painting/sculpture/music, four referring to literature. The suite presents as a mixed bag where the titular references can be helpful but – as with so many cross-discipline works – could also prove distracting. You take on trust that Liszt found inspiration in his selections from art and letters; you’d be wasting your time, I suggest, if you went looking for more meaningfulness beyond a few broad strokes.

It’s easier to keep away from useless inferences in the painting/sculpture/music pieces. For instance, Sposalizio, inspired by Raphael’s The Marriage of the Virgin, presents an insoluble problem: what’s the connection? It existed in the composer’s aesthetic reaction to the picture but you’re hard pressed to see how. Lee performs it with plenty of space, in no rush to make a temporally efficient attack on the right-hand quaver pattern that starts in bar 9; but his rubato is delicately applied, Only a few top notes get subsumed in the Più lento chorale but the double octaves leading to the piece’s high point combine care and bravado in excellent balance.

You can’t make much of Liszt’s Il penseroso either, except to presume that the composer thought the statue from Lorenzo de Medici’s tomb was given to sombre ruminations; well, so you would, wouldn’t you, given the surroundings? Even major chords in these two pages have a dour flavour but Lee performs the piece without surprises, giving full vent to its grim character and ceding no ground in the central bars 23-31 stretch where the chain of chords acquires a subterranean mobile bass.

Most music-lovers who know the Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa are aware that the actual tune was written by Bononcini whose life-span overlapped with Rosa’s by 3 years only. It’s a great march tune and quite a test to sing. Lee finds the right amount of bounce and is musician enough to exercise discretion with regard to phrasing, notably in the Sempre l’istesso setting at the piece’s middle.

With the three Petrarch sonnets – Nos. 47, 104, 123 – the listener is on familiar textual ground, assisted greatly by the fact that these were originally songs. In fact, you can go back to the composer’s first essays of 1846 and trace fairly easily the various alterations and interpolations of the 1858 piano solo version. in Lee’s hands, these pieces are highly effective, thanks to the performer’s keen eye for the fundamental melody lines and a reliable security in handling the inserted cadenzas and masking ornamentation. Indeed, the more you hear these parts of the Années, the more delights you find, like the touching expressiveness of the first vocal strophe’s restatement in G Major starting at bar 37. Lee’s handling of the syncopated vocal line throughout remains completely fluent and eloquent in its phrasing – a laudable realization of the fervent blessings that both poet and composer celebrate.

With Sonnet No. 104, we’re definitely in the land of the Liebesträume with a commanding lyrical vocal line, quiescent arpeggios and rich, mutable chord sequences. It’s not easy to see how Liszt is reflecting Petrarch’s myriad oscillations – one per line (except for the last) in a welter of conceits. Here is one place where the melody is not illustrating any leaps of imagery; it’s just one long, luxuriant line with several cadenza interruptions that Lee is inclined to treat without fireworks.

Not the least inspired of the three, Sonnet No. 123 is where Lee takes most liberties, most obviously with a stringendo starting at bar 56 which decelerates too early. As well, at various points the pianist likes to linger – extending a note’s value or allowing a good deal of space before resuming after a caesura, or taking an a piacere across the last four bars very literally. But you find just as many subtleties in this Chopin-indebted work; listen to the mild susurrus of left hand triplets that start at bar 22, or the impeccable catch-and-release of the change from E Major to C Major at bars 40-41.

In all sonnets, you hear a further testament to Lee’s insight with regard to this music and his responsiveness to their Romantic vocabulary. These soulful gems are followed by the CD’s longest track: Après une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata. To his credit, Lee gets nearly all the notes; no mean feat in this virtuosic exercise where the excitement is built up in several short-lived paragraphs as Liszt contemplates (possibly) the various descriptors of torment and vice in Hugo’s poem. This work is probably the most technically demanding that Lee attempts here; furthermore, its length makes it difficult to mould into a narrative – even more so than the second of the légendes.

For instance, I can’t find anything else on the disc to compare with the long Presto agitato assai that stretches for about 110 bars of barely punctuated action. Lee exercises his flexibility here with some split-second delays as he moves between registers, but it’s never enough to upset the onward surge of the paragraph. There’s a counterbalance to this in the shift to F sharp Major at bar 157 for a più tosto ritenuto reminiscence of Beatrice where the writing is like a cross between a Chopin nocturne and an étude. In this 23 bar episode, Lee shows a remarkably even-tempered responsiveness that gives us more than a mossy Romantic texture; rather, a subtle interplay of accents, both rhythmic and melodic, and a fine realization of Liszt’s vision of an in medias res Paradise emerging in the context of an Inferno that sounds – like Milton’s Satan – suspiciously heroic.

An all-Liszt CD from a (resident) Australian pianist is to be celebrated, of course, but not just because of the implied ambition. This is a remarkable accomplishment for its unalloyed probity; listening to Lee’s insightful readings has been one of the more memorable passages of play that I’ve enjoyed in some years of Liszt experiences. Here is a recording that stands secure on its own merits. If it’s not flashy enough or Cziffra-like for some, that’s too bad: Lee is his own man and his interpretations reveal a highly welcome integrity.

LA VIE EN ROSE

Tania Frazer, Jonathan Henderson, Alan Smith, Alex Raineri,

Saturday August 1, 2020

Tania Frazer

Latest in this online series that is lighting up the synapses of music-loving Brisbane, Saturday’s all-French concert employed the services of the city’s Southern Cross Soloists; well, four of them. While you might have expected from the title an hour-long reminiscence of Trenet, Aznavour and Piaf, what came out was both enriching and puzzling but, in synchronicity with what I have learned about the Soloists, the program was packed with arrangements – some of them comfortable for all concerned, others not so happy. At the heart of it all sat Alex Raineri’s piano accompaniment; in an act of self-abnegation, the Festival’s artistic director performed only one sols, which is extraordinary when you consider that the offerings included works by Satie, Ravel and Debussy.

In fact, the most orthodox, ‘straight’ work kicked off the evening. Henderson and Raineri worked through Francaix’s Divertimento of 1953; not a piece to keep you engrossed but an alternately tuneful and busy compendium. Its initial Toccatina, a non-stop barrage of notes for both players, proved as full of surface excitement as many another showcase written especially for Rampal; a frippery, but soon over. The following Notturno proved attractively mobile; no longueurs here. Another vital effusion in the Perpetuum mobile which lived up to its title but annoyed at the opening because you could not tell whether the rhythm was intentionally irregular or whether the players were uneasy with its metrical lay-out. Fitted with a galaxy of chromatic runs, these pages gave Richardson a real workout in terms of breathing.

I found Francaix’s Romanza the most attractive of the suite’s five movements with its deft combination of sentimentality and spice. You couldn’t call the latter aggressively dissonant but the composer beguiled you with several unexpected turns of line and harmonic structure. These pages showed Francaix at his best in a lyric of no little charm, executed without excess in any department; the unfeeling could dismiss it as film music but the final bars showed how Francaix could transcend the trite. As for the Finale, it impressed for a dash of piquancy but sounded like a trial for the performers who fortunately found a less dogged approach as the piece neared its end – or perhaps the work gained in inspiration. Whatever the case, you were more aware in the later pages of a sense of humour in the stop/start alternations and a slick final bar.

For a lot of us, there was a time when we found Satie to be as he presented – droll, eccentric, heart-of-gold. But the charm wore off somewhere in the 1980s for me; now the performance directions along the lines of ‘ Take a nap, then construct a lovers’ nest from papier-mâché and osprey dung’ seem aimless, although such high-jinks gave rise (eventually) to a school of composition where the score was all prose; and who was that Frenchman discovered for us by Keith Humble and Jean-Charles François who wrote pithy enigmatic texts as his scores? Not to mention Stockhausen in the later Messianic years. Even so, we are still brought up short by the pared-back calm of creations like the Gymnopédies in both piano and Debussy-scored (1 and 3 only) formats.

No less so by Satie’s Gnossiennes, which may have something to do with gnosticism or, more materially, with Knossos; I’ve had nothing to do with the creed but have wandered around the Cretan ruins and Satie’s miniatures could possibly have some connecrtion with Sir Arthur Evans’ excavated site – exactly what, I don’t know except for a shared angularity. Whatever the background, this performance of Gnossiennes 1, 4 and 3 saw Frazer offer her own transcriptions for oboe and piano, the outer ones of this trio very well known. Frazer took the right-hand melody line and left to Raineri the chordal background.

It took a while to get used to the penetrating double-reed timbre but Frazer generated an expressive line in No. 1, although I wondered about some of the too-simple dynamic shifts during repeats, like the move to piano in the second half of the Très luisant segment; and the upward octave shift on the final F sounded unnecessary. The encounter with No. 4 impressed in its middle strophes, after the semiquaver quibbling. And I couldn’t understand the acceleration during No. 3 unless Frazer and Raineri were putting an individual slant on the composer’s direction to play De manière à obtenir un creux. If anything, the reading of this Gnossienne seemed to me rather over-played, imposing a personality where the original intention was to remove it.

Smith gave a sensible reading of Ravel’s Tzigane with fine Raineri accompaniment across the whole tension-packed canvas. The violinist would probably not have been too happy with his A dotted crotchets in bars 9 and 10 but this whole opening section on the G string only is a taxing passage, especially as it sets a high intonational standard right from the first notes. Smith’s rendering proved powerful enough, although the double-stops at Rehearsal Number 3 emphasized the lower line. Coming up all too soon, a diabolical alternation of harmonics and left-hand pizzicato follows before the exposed violin gets some relief (not that it ever gets much of a pause).

The violinist powered through the testing pages with admirable zest, winding up with an excellent grounding deliberation at Number 17, building to a fine clamour at Number 32 with the concluding rush from accelerando to presto impressing for its accuracy under high pressure as the piece smashes into a compelling quadruple-stopped last two bars. Tzigane is one of music literature’s great exercises in deconstruction, Ravel taking all-too-familiar Ziegeuner tropes and pushing the trite into virtuosic exercises with no concern for soppy sentimentality or faux-masculine flashiness. It’s a delight to hear when the violinist is able to handle its trials and Smith did Ravel – and himself – proud.

From here on, the program moved into Beecham-lollipop mode with a bracket of three songs and a one-time compulsory encore for violinists. Raineri began this group with his own solo piano arrangement of Louiguy’s La vie en rose. It followed the song’s chorus faithfully enough, the whole piece containing only a few harmonic solecisms and, for most of its length, having a concentration on the lower half of the piano’s compass. Taking the familiar tune up an octave was effective, not least because it made for a relief from the low-pitched preceding pages. I’m not a fan of the ripple/arpeggio ending but at least it wasn’t overdone here. No, it wasn’t as ambitious an undertaking as Grainger’s reshaping of The Man I Love but it did little harm to this era-representing evergreen.

Henderson partnered Raineri in a no-surprises version of Debussy’s pre-1891 Beau soir chanson. The flautist took on the vocal part with a generously phrased volubility and giving us a well-prepared climax across bars 25 and 26. The same composer’s 1880 Nuit d’étoiles brought Frazer to the melody line. Here also, the lyric came across with ease and restraint. I think that the piano part diverged from the original in the last refrain, making the octavo jump eight bars early – or perhaps I was happy to get the main theme back pianissimo. Last in this group was the Méditation from Act Two of Massenet’s opera Thaïs, with which neglected work Sir Andrew Davis made Melbourne music-lovers familiar three years ago. Smith had no trouble dispatching this sweetest of intermezzi with a fine deftness in handling the gruppetti of five and four semiquavers that punctuate the smooth violin line’s progress in the piece’s outer sections. Possibly the sforzandi at the più mosso agitato direction from bar 34 on could have been pulled back to a less full-on dynamic level but it was difficult to find fault with the rest of the score, Raineri having little to do beyond outlining the harp’s almost non-stop accompanying role.

To finish off the night with some fireworks, Raineri and Co. put on a more taxing encore piece, a work that occupies a dodgy zone between definite program material and something frivolous with which to delight any audience: Saint-Saëns’ Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso. But, rather than employing Smith’s expertise, the work was given in an arrangement by Frazer where flute and oboe share the solo violin line between them. Frazer took the opening solo up to bar 6; Henderson took over from bar 7 to bar 10; and on it went in a heart-warming demonstration of how to play musical fair-shares. A little bit of transposition was needed to cope with the fioriture nine bars before the rondo’s start. Nevertheless, once the main constituent of this work was in progress, Frazer maintained her even distribution of the work-load with some clever interweaving and a subtle preparation for the trill hiatus just before Letter B.

Notably appealing was the attack by both woodwind artists on the double-stops during the con morbidezza interlude. A crunch-of-sorts came with the triple-stop cadenza five bars before Letter G which turned somehow into spaced-out arpeggios; but that’s pretty much what the original is. Then on to a hurtling coda and home. You’d have to call it an interesting exercise but I have to confess to a longing for the original where you get to enjoy a violinist’s handling of the composer’s hurdles, contrived especially to test that instrumentalist’s virtuosity and self-control.

Not a night for the purist, then. Still, Raineri had organised a well-assorted program, contrasting the tried-and-true with some arcana, peppered with three very popular works. All of it gave a platform for four sadly under-used musicians. But we live in hope that Aunt Annastacia will keep us free from extra-state contamination and that these artists will soon get back to playing for live audiences who are actually in the room with them. Until then, we will have to put up manfully and womanfully – and appreciatively – with the inbuilt fluctuations in content of entertainments like La vie en rose.

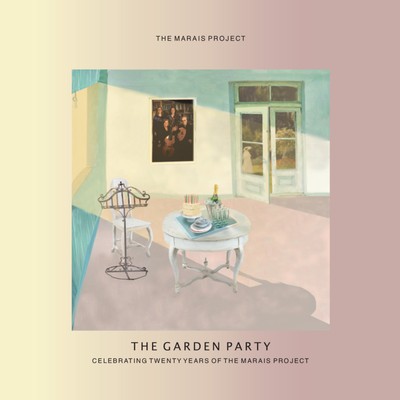

THE GARDEN PARTY

Move Records MCD 592

Talk of accordions, and they spring up all over the place. No, perhaps not all over but, as the Fates would have it, James Crabb appeared in last week’s bonus recital from Musica Viva; straight after, this Marais Project CD came up for attention and it features piano accordionist Emily-Rose Šárkova as both performer and arranger, appearing in seven of the 19 tracks. Of course, the instrument is up against it for a lack of original material in the serious music field – sorry: established original material – but one way to get around this is to insert your contribution into a biddable ensemble and see what comes out.

Here, Šárkova has been invited by the Project founder Jenny Eriksson to enter the wide-ranging ensemble and imbue the company sound with her own. We start out with Eriksson’s own take on the Feste Champêtre from Marais’ big Suite d’un goût Étranger, included in the composer’s Livre IV for viol and continuo. I’ve spent a while listening to a few versions of the original, following the viol throughout, this research illuminated through a brilliant execution of the piece by Jordi Savall. There seems to be little thematic cross-referencing between Marais’ earthy rondo and Eriksson’s The Garden Party; not that you can read too much into that. As well as the accordion’s penetrating timbre, you have Eriksson herself on gamba, Project regular Tommie Andersson‘s baroque guitar, and the all-important violin of Susie Bishop.

Like Marais’ Feste, the Party is initially in a 4/4 rhythm with a long detour into triple time. You hear a recurring root passage in both pieces that demarcates the variants/episodes in the earlier work and acts as a framing device in Eriksson’s reappraisal. And while the 18th century piece’s various sub-divisions feature an appropriate musette and a tambourin, the title track doesn’t take too long before venturing close to the world of klezmer. Later, a few jazz-inflected passages imitate Stephane Grappelli too close for comfort . . . or perhaps the aim was to summon up the French-Italian violinist’s spirit on purpose. One of the modern variants features the gamba and accordion (single-line) in collaboration; another has violin and gamba; later gamba and guitar, before Bishop invokes the Grappelli spirit and we re-enter the klezmer mode.

Still, it’s a party and you’d be insane if you went looking for a thematic consistency at one of those events these days. More to the point, Eriksson’s celebration is crisp and determined in every bar, complete with bracing accordion chords to interpolate some well-placed full-stops.

Next comes another arrangement by Šárkova of four pieces from the E minor Suite from the 1717 Livre IV by Marais. We hear the Rondeau Paÿsan, jump back to the Sarabande, then hear the two characteristic pieces that end the suite: La Matelotte and La Biscayenne. By this stage, you’re hearing (or imagine you are hearing) repetition of material between pieces – or perhaps you think it’s so because of the multiple repeats. In any case, the arrangement is for gamba and accordion and it works pretty well because Šárkova is a deft hand at picking out melody lines to meld into and contrast with Eriksson’s part. This is particularly effective in the Sarabande where the contrast in sonority between both instruments is nowhere near as clear-cut as you’d expect.

An O salutaris hostia by Pierre Bouteiller (no, me neither) uses Danny Yeadon‘s gamba as well as Eriksson’s, Andersson’s theorbo, while the text is sung by soprano Belinda Montgomery. This is, for my money, the finest product on the CD but it’s a re-issue from the group’s previous recording from 2009, Love Reconciled. The vocal work is refreshingly clear with just enough ornamentation, while the supporting lines make a splendid and mellow mesh. Such a pity the composer didn’t extend to Aquinas’ second verse with its terse and moving last couplet.

The Suite No. 2 in G minor of 1692 by Marais here uses Melissa Farrow on baroque flute, partnered with Fiona Ziegler‘s baroque violin, while Eriksson and Andersson make a firm continuo duo. Once you get used to the convention of treating six regular quavers as changeable into dotted quavers+semiquavers when the mood takes you (yes, that’s just being flippant about a well-established Baroque convention), it’s a pleasure to hear the upper lines move in polished synchronicity. This is another recycling, from the Project’s 2015 Smörgåsbord album, giving us four out of the 13 pieces in the suite itself: Prelude, Rondeau, Plainte and petite Passacaille. All are cleanly accomplished, although I missed the repeat of the Rondeau‘s second part, but delighted in the slow processional of the Plainte, and listened over and over to bars 67 to 65 of the petite Passacaille for the brisk inter-cutting between flute and violin.

Performing J’avois crû qu’en vous aimant, an anonymous petit air tendre, all participants get to run through the theme – Andersson on theorbo to start, then Bishop singing two of the three verses and playing one, Eriksson giving an elegant shape to her outline. All of this is convincing as a mobile plaint, bu I was sorry to have to forego the final section that moves into triple time and breaks the mood, like the third Agnus Dei in so many of those Classical period masses. Still, the MP isn’t alone in that as all other groups I’ve heard attempting this piece also avoid any bucolic suggestions.

Another recycled group (from the group’s Love Reconciled CD of 2009) follows with a selection from Marais’ Livre V of Pieces de violes, Eriksson taking prime position, supported by Andersson on theorbo, Catherine Upex supplying a gamba support, and Chris Berensen the most discreet of harpsichordists. The quartet begins operations with an unexpected preface in the Rondeau louré from Livre III, which accretes instruments as it passes by. then the Allemande la Marianne, a sarabande where the theorbo and second gamba sound very forward, a menuet in which the melody line barely survives the accompanying chords’ ferocity, and La Georgienne dite la Maupertuy which brings an appealing brusqueness of articulation to the fore at each repetition of the main theme.

Last of the previously-issued numbers is Andersson’s arrangement of the Swedish tune Om sommaren sköna which comes from the previously-mentioned Smörgåsbord CD. The executants are tenor Pascal Herrington, Farrow, Ziegler, Eriksson and, of course, Andersson. Nothing new here, again: Andersson leads the way with a solo theorbo rendition of the tune, followed by Eriksson doing the same. Then Herrington sings the rather doleful C minor tune’s first verse before Ziegler has her way with it, supported quietly by Farrow before the tenor comes back with verse three, Farrow very subtly shadowing him. Sorry to miss out on the middle Där hörs en förnöjelig stanza, particularly because the melody suits Herrington’s clean-edged voice. But then, while wishing the best to all concerned, there’s not much you can do with a tune like this except play it over and over – unless you’re prepared to take it out on a limb and provide some real variation.

The Project winds up with two jeux d’esprit that bring Šárkova back into the fold. First is her arrangement of La Anunciación by Ariel Ramirez, sung by Bishop with the piano accordion dominating the perky accompaniment to the Argentinian composer’s Christmas song; Eriksson and Andersson are assisted by double bass Elsen Price and Šárkova takes on a short singing role. It’s very upbeat and happy – and short, because the performers only deliver half of the Félix Luna verses. To finish, we have De fiesta en fiesta, a catchy chacarera (or is it?) by Peteco Carabajal where yet again the performers dig deep to find their inborn Argentinian. The personnel is the same as for La Anunciación and, as has latterly become prevailing practice, the theme gets shared around between the singer and violin with lots of interstitial commentary from the accordion; even the gamba pokes its head above the battlements for a short while and Šárkova joins Bishop for the last quatrain although, as in the previous number, only half the verses get a run-through.

The South American brace brings this celebratory CD to a rousing conclusion as the Marais Project rings up 20 years of operations with some new material and a recycling of their favourites or works that have found favour with MP supporters. Even if you’re so-so about the outer tracks in this album, you get to re-experience these players at their best in previous releases. And, when they’re good, they’re very, very good.

Bendooley Estate, Berrima

Monday July 20, 2020

James Crabb

Julian Smiles

For its bonus recital in the middle of a year that can politely be called ‘unsettled’, Musica Viva hit on a duet combination that you would be charitable to view as made in Heaven. In fact, matching a cello with an accordion, no matter how classical, is a dangerous affair because the string instrument doesn’t have commensurate carrying power and, although it can quadruple stop, the cello also doesn’t have the ability to hit note clusters. Put them together and you’re asking a good deal from the accordionist in terms of dynamic subtlety.

My only previous experience with James Crabb has been through his excursions with the Australian Chamber Orchestra, with which body the Scottish musician has been a welcome guest, particularly in those years when Richard Tognetti and (some of) his ACO colleagues were engaged with the music of Astor Piazzolla, that Argentinian-born fecund source of encore material. In fact, the relationship between Crabb and the Sydney players goes back to at least 2003 when the accordionist and pianist Benjamin Martin appeared as guest soloists on the CD Song of the Angel with members of the ACO. If you like your tangos feisty to the point of violence, here you go.

Smiles is a more familiar figure in Australian concert and recital halls. One of the originals in the Goldner String Quartet (what’s the point of writing that? They’re all originals, staying together as a group since its establishment in 1995), he has also been heard as a guest in Kathryn Selby’s recital series, Selby & Friends, and for some years as principal cellist with the ACO. Also to the point, he has enjoyed a long association with Musica Viva, as an educator as well as a Goldner.

On Monday evening, the duet played in a lavishly wooden space at the winery, looking to me like a sort of warm version of the Riddling Hall at the Yarra Valley’s Domaine Chandon where Musica Viva presented a brilliant series of mini-festivals for some years. In democratic spirit, both artists took it in turns to address their audience, which process was remarkably free from the awkwardnesses and staginess of most procedures of this kind. Unlike the Melbourne Digital Concert Hall practice, this recital had no program: you found out what you were going to hear just before the players set to work. So Elena Kats-Chernin’s Slicked back Tango came on before you knew it was in the offing.

Luckily enough, this dance was based on an arrangement for cello and piano by the composer, one of eight versions she has put out; no wonder her works’ catalogue is so vast. This wide-awake writer is familiar with all the tropes of the South American dance, giving the cello pretty much all the melody material with the accordion taking on the chordal/rhythmic responsibilities, Crabb considerate in letting his partner take up prominence. It’s brief and lively, a pick-me-up like we had in the mid-20th century when the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra used to whiz through Glinka’s Ruslan and Ludmilla Overture to open otherwise stolid concerts.

This short work was followed by a well-known cello solo: Bloch’s Prayer – first piece in the triptych From Jewish Life. Once again, Crabb did piano duty although you missed quite a few bass notes; one moment they were there, then omitted in the next passage. Smiles kept the right side of schmaltzy, except in the Più vivo of the last 7½ bars which was overdrawn, as was the over-loud accordion chord in the 4th-last bar. But neither player treated the work as a chain of glottal stops, avoiding surges of loud and abrupt drops to soft, or imposing extended time for the melismata interruption near the end or for the chains of shared triplets.

At the heart of this recital came C. P. E. Bach’s Viola da Gamba Sonata in G minor H. 510, the most successful of the night’s collaborations in terms of sound colours. Crabb impressed right from the beginning of the Allegro moderato, taking on his two cembalo lines with brisk vigour and giving each one equal weighting, especially welcome in his negotiation of Bach’s infectious ‘walking’ left-hand bass. Both players performed with a mutually shared suppleness of rhythm without disturbing the work’s underpinning pulse. Of course, they had top-notch material to work with; not just that safe-as-houses bass but also a wealth of melody intertwined with a fluency that delights at every turn.

In the C minor Larghetto, you had time to take in the work’s detail more easily, as in the delineation of all the original’s ornamentation. While the players interwove their melodic work, you had even more leisure in which to appreciate Bach’s fertility, ideas thrown off with as much insouciance as in a mature Mozart piano concerto. Smiles gave us a pointed and carefully shaped reading, Crabb keeping his potential swamping power well under control, most notably in the melting 6ths across the final 8 bars of this semi-siciliano.

A different sort of pleasure came in the concluding Allegro assai where Bach pulls some subtle rhythmic tricks across its length. Crabb did a sterling job of realising the figured bass chords during the movement’s first 11 bars before his treble entered to compete with the viol/cello. My only disappointment came with the executants’ decision not to repeat the second half of this segment of the sonata.

Having heard Bloch’s Prayer earlier, now we were treated to the other side of the religious coin in Saint-Saens’ Prière Op. 158, a product of his last years originally for cello and organ. You could not fault the grace of expression in the opening section but the change to E flat soon saw an influx of religiosity, notably when the cello started on its triplets in bar 38. A little later, the cello’s two-quaver pattern treatment veered towards the sentimental and the piece’s climactic point at bars 69-70 entered into the composer’s theatrical over-kill with enthusiasm; not to mention the reminiscence of Samson at bars 91-94 which sounds cheap in this context. However, the problem with this reading came from the accordion’s texture which couldn’t avoid sounding very reed-heavy; to be expected, given the nature of the instrument.

Last scene of all was the inevitable Piazzolla; we’d had balancing prayers, so why not balancing tangos? This was Le Grand Tango of 1982, the one written for Rostropovich who was unaccountably slow to come to the party and play it. It’s a long piece, well over 10 minutes, and here gave evidence of a marriage of vision even if you might have liked more vim from the cello. Nevertheless, both parties were consistent in their observance of the many incidental passing notes throughout. Here, the nuevo tango is writ large with plenty of individual segments contributing to the whole. At its core, it strikes me as concert music, not the sort of thing you can easily dance to unless you’ve been pre-choreographed – which, for all I know, may be essential to this new style. But Smiles and Crabb gave as sensibly aggressive an account of this score as you could want with firm agreement on their attack, speeds and dynamic variation.

You could quibble that a cello is not strong enough to carry the burden of Le Grand Tango; that you need a violin to realise the dance’s inbuilt eroticism; that giving a melody to any bass instrument is dangerous when you have a bandoneon/accordion on the loose. But, as in the Bach gamba sonata, Crabb observed the decencies: letting rip when he had the running, but maintaining a backing role when Smiles took up the Hauptstimme. For such an odd combination, one where the members had no original music for cello and accordion in their rucksack, these artists delivered a near-hour’s worth of exemplary duo-playing.