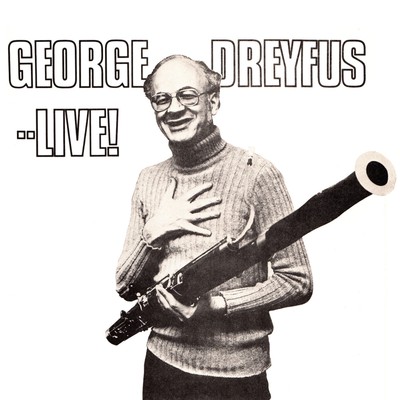

GEORGE DREYFUS . . . LIVE!

George Dreyfus and Paul Grabowsky

Move Records 3300

Next year, George Dreyfus will turn 90. On the current Australian music scene, he regards himself as a true rara avis, in that he seems to be one of only a few survivors from that halcyon period when this country discovered best European practice and the creaking shackles of musical composition – as taught by transplants from British academia – started to buckle. Unarguably, many of the Bright Young Things of that Golden Age from the 1950s to the 1970s have passed on: Don Banks, Ian Bonighton, Bruce Clarke, Ian Cugley, Ian Farr, Eric Gross, Keith Humble, Richard Meale, James Penberthy, Peter Sculthorpe, George Tibbits, Felix Werder and Malcolm Williamson. And their own near-predecessors have definitely left us – John Antill, Clive Douglas, Peggy Glanville-Hicks, Raymond Hanson, Robert Hughes, Dorian Le Gallienne and Margaret Sutherland.

But some of the Dreyfus-contemporary generation are still loitering, like Alison Bauld, Anne Boyd, Peter Brideoake, Colin Brumby, Nigel Butterley, Barry Conyngham, Ross Edwards, Helen Gifford, David Lumsdaine, Larry Sitsky and Martin Wesley-Smith. Admittedly, some are lingering quietly, outwardly content after the highs and lows of careers in composition. Dreyfus can not be numbered among these but is still writing, still revelling in every performance of his own work, still kicking against the pricks.

The alphabetical lists above follow the contents page of a volume to which Dreyfus refers in his notes for this CD: ‘James Murdoch‘s piss-weak 1972 Australian Composers picture book’ – about which, more later. If I were to follow Frank Callaway and David Tunley’s study published six years later, Australian Composition in the Twentieth Century, the well-gone group would extend to Edgar Bainton, Arthur Benjamin, Moneta Eagles, George English, Felix Gethen, Alfred and Mirrie Hill, Dulcie Holland and William Lovelock; John Exton and Eric Gross would feature among the BYTs, while Jennifer Fowler and Donald Hollier are survivors.

Andrew Ford’s Composer to Composer (1993) casts an extra-Australian net but the locals he includes number the very-much-alive Gerard Brophy, Moya Henderson and Liza Lim.

All of which is to say that Dreyfus is not starved for company but he is, of all the composers listed above and still at work, the oldest – in many cases, by more than a decade.

This CD is a re-release of a 1978 LP, so it’s offering nothing new except the opportunity to drink old wine from a new jar. The works – all short – cover the period from 1957 to 1978, the largest number coming from the 70s . . . as you’d expect. Dreyfus himself plays bassoon and sings enthusiastically; for the nostalgic among us, memories come seeping back, encouraged by the composer who starts off with his most famous creation: the title theme to Rush, a TV series set on the Ballarat Goldfields brought to vivid life in a hurtling, catchy tune which is actually infiltrated by little quirks that come across loud and clear in this reduced version for two instruments.

The following track also features an early success: the main theme to a children’s TV series, The Adventures of Sebastian the Fox, which had the significant advantage of being singable. And so it was, by flocks of engrossed young admirers. After this comes a sort of lucky dip of pieces that can be handled by two performers, among which is a heavy representation from film scores, a form that the composer found most congenial: the main title from the ABC commissioned Marion of 1973; the theme of Ken Hannam‘s post-World War One film Break of Day; another 1976 creation in music for another film, Let the Balloon Go. This same productive year also saw the appearance of Power Without Glory, a 26-episode serialisation from the ABC of Frank Hardy’s controversial novel. Dreyfus provided the score for this ambitious undertaking; and there’s a small scrap called Peace, the lone survivor of a Film Australia production in 1969 called Sons of the Anzacs.

Dreyfus and Grabowsky give these samples of the composer’s music without flourishes, the amiable melodies scaled down in effect from the lavish treatment they are given on a composer-conducted CD The film music of George Dreyfus, Move Records MD 3098 which holds them all.

As for the singing, Dreyfus treats us to his Ballad for a Dead Guerrilla Leader, a segment of his opera The Gilt-Edged Kid which was commissioned in 1969 by the national opera company but never performed by it: God knows why – this extract is falling over itself with accessibility and, when you consider the thousands of dollars lavished on models of local-grown tedium that appeared on Opera Australia’s playlists in later years, you have to wonder about the perceptual frameworks of the apparatchiks involved and their selection criteria.

The earliest track on the CD is Das Knie, part of the early (1957) nine-part setting of some Galgenlieder by Christian Morgenstern. Song of the Standard Lamp comes from a 1975 collaboration between Dreyfus and Tim Robertson, The Lamentable Reign of Charles the Last, written for that year’s Adelaide Festival. Finally, Dreyfus sings his Three Ned Kelly Ballads, with texts by film-maker Tim Burstall but, like the other sung works, without their original accompaniment. Dreyfus’ vocal quality is best described as honest rather than burnished by years of training and Grabowsky’s keyboard contributions support his collaborator without attracting much attention.

Apart from the Ballads, the longest work on offer is Deep Throat, a work of no little oddity. Offended by Murdoch’s evaluation of his Symphony No. 1, Dreyfus put together a short two-page score (reprinted in the CD’s accompanying leaflet) consisting of scraps from Murdoch’s commentary given a mundane vocal setting alongside scraps from other sources – Mahler, Bruckner, Beethoven, the composer’s own symphonies – the most dismissive of Murdoch’s statements coming in for special repetition. The score comes complete with performing instructions which basically amount to open slather, to the point where players can introduce whatever they feel is fitting, i.e. any other symphonic scraps that strike a performer’s fancy; Dreyfus himself brings in a bit of Tchaikovsky’s F minor Symphony.

Deep Throat is a satire, poking fun at the aleatoric practices of mid-20th century advanced composers and charlatans alike. The humour is far from subtle but the sense of anger is obvious enough. As you’d expect, the work isn’t meant to travel far outside the world of contemporary Australian composition in the late 1970s. Far more interesting is to re-visit Dreyfus’s Symphony No. 1 with Murdoch’s pallid observations in mind; here, the composer’s justification rings with resonant force, particularly throughout the powerful Moderato finale.

At the end of the CD, what you have enjoyed is a small retrospective; even for its time, it was light-on in content and length (a bit over 33 minutes). It’s unlikely that even as well-disposed a company as Move Records has the resources to re-issue some of Dreyfus’ sterling works, like the Symphony No. 1, From Within Looking Out, Jingles, The Seasons, the Noverre Wind Quintet, the Sextet for Didjeridu and Wind Instruments, And what of the operas that have been produced successfully overseas – Rathenau and Die Marx Sisters, both of them over 20 years’ old and not a note of them heard here? Furthermore, I haven’t mentioned (so far) other small gems like Larino, Safe Haven, Lawson’s Mates or Waterfront that have enriched that ever-stretching shelf that holds the Dreyfus catalogue.

This brief remembrance of things past is welcome yet it can’t help but bring to mind a larger canvas, one that deserves re-viewing and so shining a light on the major role that Dreyfus played during a strikingly productive era in this country’s serious music life, a time that many of us recall with affection and respect.