A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC

Melbourne Chamber Orchestra Virtuosi

Deakin Edge, Federation Square

November 20, 2015

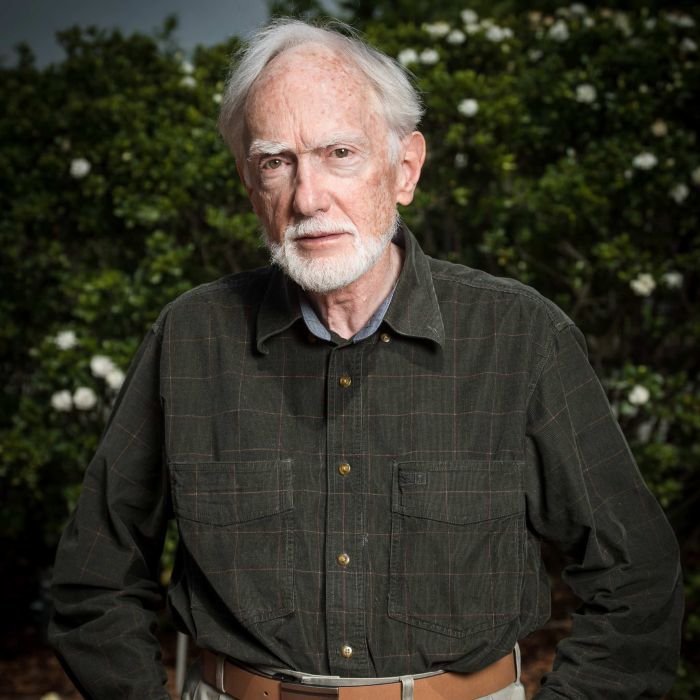

A new group on the local concert-giving scene – well, new to me – the Virtuosi has spun out of the MCO ranks over the past year or two and comprises some very familiar faces. The central organization’s artistic director, William Hennessy, heads the second violin trio, Lerida Delbridge from the Tinalley String Quartet is Virtuosi director, the violas are veterans Justin Williams (also a Tinalley member) and Merewyn Bramble, cellos Michael Dahlenburg and Paul Ghica (Bramble’s colleague in the Patronus Quartet), and the double-bass-of-all-work is the dependable Emma Sullivan.

Last night’s program, to be repeated tomorrow in the Melbourne Recital Centre, impressed as a consolidation of core repertoire for a string ensemble of modest numbers. A tad circumscribed in personnel for string orchestra staples like the Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 (which needs a third viola and cello) or Vaughan Williams’ Tallis Fantasia (its subdivisions require extra personnel in every section), the group still contrived to put together a successful sequence of familiar works stretching from Boccherini and Mozart, through Tchaikovsky and Holst, to a new work by Australian writer Nicholas Buc with the provocative title A Little Night Music and set alongside Mozart’s sparkling serenade of the same name.

The Virtuosi began with the expatriate Boccherini’s appreciative Night Music on the Streets of Madrid, although I missed hearing the first segment dealing with the Ave Maria bells as the performance seemed to launch straight into the Soldiers’ Drum phase, two violins doing the honours in that phase from opposite sides of the Edge’s internal walkway. But the main segments showed a well-rehearsed body with an appropriately fluid approach to rhythm; the only question arose in the Passa Calle where Dahlenburg’s solo melody line could have been projected with more aggression, particularly as the chief accompanying texture was pretty much continuous pizzicato.

In fact, the night’s soloist was Dahlenburg who took the central role in both Tchaikovsky offerings: the Nocturne and that melting moment, the Andante cantabile from the D Major String Quartet No. 1 in Tchaikovsky’s own arrangement which moved the pitch up a semitone, it seems, but graciously gave the cello an opportunity to play the folksong-indebted theme that it alone does not get to treat in the original score. The solo strand travelled well in the Edge’s large air-space, with only a moderate vibrato employed and a fine sensibility brought to bear that let the music speak for itself, more clearly in the Andante than the Nocturne where the accompaniment, well-intentioned and firm, was overbearing in the piece’s later, mildly decorated pages.

Both the Eine kleine Nachtmusik and Holst’s St. Paul’s Suite enjoyed sterling interpretations, the Mozart cleanly executed with loads of animating dynamic variety and supple phrasing, especially in the simple but demanding Romanze where the violins resisted its temptation to gild the melodic lily. Later, the English suite featured fine solo work from leader Delbridge and Williams’ diplomatically understated viola in the Intermezzo that alternates languour and ardour in just a few brilliant pages. For both of these essential scores, the musicians spoke with impressive unanimity, realizing the promise shown before interval in a high-spirited run-though of Mozart’s F Major Divertimento K. 138 – another necessity for any string orchestra to have under its belt.

Buc’s new work has few obvious problems for its interpreters. The work’s content is neatly constructed, the phrase-lengths predictable, its atmosphere suggestive of a standard film noir accompaniment – moody but not tragic, unabashedly lyrical, high on string colour, no pretensions to depth of meaning. Buc has constructed an amiable nocturne and the Virtuosi, with the backdrop of several regional performances behind them, gave it a confident airing. As a commissioned foray into modern music, A Little Night Music represents a tentative enough move; now for more challenging fields – Schoenberg or Tippett, anyone?

La Compañia (image: lacompania.com.au)

La Compañia (image: lacompania.com.au)