THE SLEEPING BEAUTY

Playhouse, Arts Centre Melbourne

March 11, 14, 15, 17 and 18, 2017

The King

Much has been made of the costumes and puppets in this new production from our state company; plenty of effort has been liberally expended on this area, each of the central characters having a ‘front’ figure manipulated by puppeteers as well as a singer in modern-day mufti to sing Respighi’s notes. This conceit is sustained right up to the end when the figures of Beauty and her Prince appear for the final hurdles, each pretty much en clair apart from some masks that disappear post-kiss.

Joe Blanck‘s designs for these manipulated figures are a random collection, the best of them that for the King. Some of the others are depressing to look at, reminiscent of the trolls in Peter Jackson’s first The Hobbit film; among these I’d include the Ambassador and his Trumpeter, and the Old Lady who holds the fatal spindle that brings on the story’s central disaster. Having noted this unsettling quality to some figures, and the disturbing Japanese ghost shape allotted to the benevolent Blue Fairy, I’ll allow that others have a Saturday-arvo-pantomime appeal, like the sprightly chorus of frogs at the opera’s start, the spry Jester-in-the-form-of-a-cat, and the plot-recapping Woodcutter who takes the shape of a lumbering, stage-dominating tree.

It all makes for a mobile scene sequence; for the most part, the story unfolds visually quite well, apart from the lengthy action for birds on flexible poles during the first pages and the following florid duet for Nightingale and Cuckoo, as well as the unavoidable longueur as the castle goes to sleep for four centuries.

Of more importance, the company’s musical work maintains a high level throughout the work, with only a few bumps along the way. Conductor Phoebe Briggs and director Nancy Black have elected to run the three acts into a single sitting; not that such a move is a disadvantage to anyone as the cast exposure shifts all the time and any orchestral tutti sticks out obviously in this voice-focused composition.

I think that the company has opted for the original 1922 scoring which calls for a celesta and harpsichord. But Tom Griffiths could also be heard on piano, which instrument comes from the 1934 revision. Whichever it is, the band – made up largely of guest musicians – played this lyrically attractive neo-Romantic music with lashings of sentiment at the right spots, the body gifted with a clean brass trio and a small group of well-attuned strings.

As for the singers, their position was quite favourable. Uncluttered by costumes and heavy make-up, leaving all the physical work to the puppeteers, they could concentrate on vocalising and remain assured that most people were not watching them. The Nightingale/Cuckoo duet that begins the opera in a lush field of impressionism found Zoe Drummond and Shakira Tsindos sharing the labour – and the pages are not easy; although not asking for dynamic projection, they do hold an amount of fioriture that is high and exposed. Timothy Newton made a clear and definite Ambassador, although he couldn’t avoid being handed a pretty bland characterization to deal with. Elizabeth Barrow‘s Blue Fairy enjoyed a fair amount of exposure – responding to the Ambassador’s request, presiding over the gift-granting to the Princess, then ameliorating the curse.- keeping a calm control over another high line, albeit one that tended to legato delivery.

The first familiar voice I heard was Timothy Reynolds singing the Jester, then later appearing as the cameo American, Mister Dollar, in Act 3. A secure technique and vocal personality made his appearances welcome, especially as both were amusingly carried off in a production that occasionally tried too hard. As the maleficent Green Fairy, Juel Riggall did a great line in irrational rage, her part not actually musical but full-bore declamation. Singing the King, baritone Raphael Wong managed to match his bluff vocal colour with the benign if gruff-looking puppet figure – another escapee (one of the dwarves?) from The Hobbitt. Sally Wilson sang two roles, the Queen and the Cat, but the first proved vocally uninteresting, notably in the Act 2 crisis, while the feline impersonation sounded over-loud and overdrawn. Another two-role singer, the experienced mezzo Liane Keegan gave fine service as the Old Lady with the spindle, and had much less to do in the (normally soprano) part of the Duchess whom the Prince discards once he gets a whiff of the sleeping Princess.

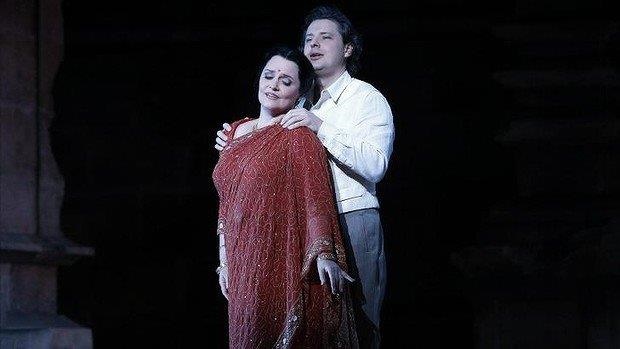

Another familiar voice emerged in Act 2 with Jacqueline Porter lighting up the stage by means of a sparkling salute to spring as the Princess, bounding wilfully into the spinning process, sinking into a coma with suitably failing vocal strength, then rounding out her night in a shapely love duet. Becoming a regular in the Victorian Opera lists, Carlos E. Barcenas sang a charming, ardent Prince, holding his own against a very active puppeteer (Vincent Crowley?) whose Douglas Fairbanks athleticism was well-matched by the tenor’s vehement but controlled power. Finally, Stephen Marsh blazed out the Woodcutter’s solo with a beefiness that suited the physical proportions of his arboreal manifestation, a broad passage of play that succeeded mainly through Marsh’s ability to make the already known assume an unexpected interest – although a good deal is owed to Gian Bistolfi‘s lines at this point.

At the end, the work was greeted with general acclaim even if it was difficult to categorize what we’d experienced – if you wanted to. It’s definitely an opera, full to the brim with splendid vocal writing and some superb moments for orchestra, notably at hiatus points in the action and least of all when Respighi satirises the dance music of his own age. But then, it’s an opera and also a mime-show. Blanck’s puppets are the stage’s focus and, with that in mind, the production might have gained by having the singers do their work from the pit, as I think was done in the original presentations by the Teatro del Piccoli ; in this space, not much would have been lost. As things turned out, the schizoid depiction of most characters left you a touch bewildered at points where the verbal action ratcheted up a notch or three.

And what of the vision behind the presentation? The set remained pretty staid, with some tapered drums and circular platforms providing the framework for activity. Philip Lethlean‘s lighting plan veered to the gloomy until Act 3. Yet the guiding spirit was certainly to amuse; no secret messages emerged – no ironic hints at subtle meanings or underlying depths to the characters. What you see here is all there is – a relief when you consider what Helden-direktoren inflict on us under the slimmest of pretexts. Sung in Italian, with translations projected on side walls, the performance makes clear efforts to cater for all audience members.

Yet the work remains earthbound; the magic isn’t calculated to generate wonder and the stage-pictures show few signs of adventurousness. However, this is an enterprise well worth visiting, if only because you’ll never see this Sleeping Beauty performed live again, I should imagine, and the musical values on show in this presentation are solid.