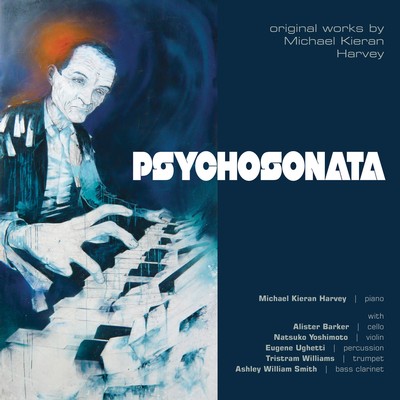

PSYCHOSONATA

Michael Kieran Harvey

Move Records MD 3368

Composer/pianists weren’t thin on the ground in the 19th or even the 20th centuries, times when the modern instrument came into its own as the instrument of choice for postulant musicians, even if it’s been superseded by the guitar over the last 50 years. The species is not unknown in Australia. There’s the grandfather figure of Grainger leading the team, with Dulcie Holland, Miriam Hyde and Malcolm Williamson a few decades later. Keith Humble knew his way round the keyboard, as does his near-contemporary Larry Sitsky. Richard Meale comes to mind for his famed Messiaen interpretations, although I never heard him play his own work. Carl Vine is an outstanding representative of this cross-over musician type. But the younger creator-performers remain an amorphous quantity – plenty of composers but few are exponents of their own creations for piano.

Then there’s Michael Kieran Harvey who has set the bar for virtuosity in this country for about 25 years, with the capacity to turn his hand(s) to anything he’s asked. A generous exponent of other writers’ works, he shows on this CD that his compositional craft is just as formidable. Mind you, much of this music speaks to Harvey’s actual pianism: restless, driving, dexterously complex, reminding you at every turn of his live concerts and recitals where the act of music-making becomes startlingly physical as the material gushes from the piano in an unstoppable stream, whether it’s Brahms or Bartok.

Harvey takes part in all seven works recorded here. He opens with the longest construct, his Psychosonata, Sonata No. 2. Its title is due to the work’s commissioning by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, the first performance coming at that body’s Hobart conference in 2012. Divided into three movements, it begins with furious action that does not let up; even when the dynamic level reduces, Harvey’s fingers keep flying. The composer’s notes refer to sonata form and every so often you feel a developmental pattern – but mostly not; rather, episode follows episode with the spirit of Bartok looming large through the work’s percussiveness and use of ostinati. As for the work’s language, it presents as enthusiastically atonal, with concords intentionally avoided. At points, the right hand action is impossibly mobile; you cannot conceive how the action is sustained for so long. Sill, the sound is splendidly engineered, catering for Harvey’s tendency to work simultaneously at both extremes of the keyboard and producing a clear-speaking mix.

The work’s movements meld into each other, so that the slower second one is upon you without notice. A more passive emotional atmosphere prevails, the activity conducted above a resonantly gruff bass register continuum for some time; the advance goes slowly with insistent decorative interpolations in the treble that move to rapid scale passages in both hands before a return to aggression at about the 3:20 mark. Yet Harvey maintains a discipline over any outbursts, while not letting go of the expressionist nightmare his musical scenario proposes here, passages of near-placidity merged with obsessive freneticism.

The final movement moves straight back to the athletic vaulting of the sonata’s opening. After a temporally confusing introductory few pages, it settles into a triple metre – Harvey’s concept of a vivace gigue , possibly. The lava flow is disrupted by relieving interludes, moderate in attack and fluency. Even in the last pages where the activity halts for isolated blurts, the underpinning restlessness is never far away. Yet, as a picture of psychopathic or psychotic thought processes, the sonata presents as organized and directed, its processes too purposeful to convince the listener of any erratic mental depictions.

Cellist Alister Barker collaborates with Harvey in Kursk, referring to the Russian submarine that sank in the Barents Sea in 2000 with all hands killed. This duet has the piano generate a relentless underpinning, as though the sonata is being revisited. Barker’s cello line presents as angular, sharp-edged writing. The work is clearly speaking in anger, in protest as both instruments remind you of racing pulses reacting to the catastrophe. This moves to a lament that suggests life dwindling, the souls’ candles extinguished. A cello cadenza rises to an uncomfortably insistent high sustained note and the last moments revert to the aggression, the string instrument executing a rising scale with double-stop support while Harvey’s piano smashes out punctuating chord clusters, the whole ending with a fierce assertiveness and insistence: you don’t forget, you can’t forget.

Fear, the disc’s second-longest work, features violinist Natsuko Yoshimoto. Harvey takes his impetus for this duet from Bertrand Russell’s 1943 An Outline of Intellectual Rubbish, citing a paragraph that concludes with the philosopher-mathematician’s well-known observation: ‘To conquer fear is the beginning of wisdom . . . ‘ Which is fine as an aspiration, an ambition, although this piece’s tone appears to be more neurasthenic than the disc’s eponymous sonata. The keyboard is confined to the upper part of its compass as it escorts the violin through various characteristics of a fearful state – a nervous tic, an urge towards hysteria, a burst of compelling trauma. Yoshimoto works through several cadenza-type passages that present aural images of nervous twitching, a teetering on the edge of control, until the violin is left alone at the end, a single voice that doesn’t reach any resolution.

For Melbourne pianist Stephen McIntyre’s 70th birthday four years ago, Harvey produced his Mazurka, which has traces of the more heroic products of Chopin, with one absolute quote near its end from the B flat Op. 7 piece. Both an ebullient and a neat tribute, it is unabashedly more representative of the writer’s personality than that of the dedicatee.

A four-movement Homage to Liszt continues the references to Harvey’s virtuoso composer forebears. With Eugene Ughetti‘s percussion seconding the pianist’s assured bounding, the opening Ballade attracts through its jazz-influenced starting pages, its liveliness punctuated by a reference or six to actual Liszt pieces. The following Waltz seems to be nothing of the kind, even if the piano and drum-kit partnership makes an infectious combination; the Harmonies du soir study is discernible if you stretch your ears. A Csardas offers a brisk parody of the Hungarian dance, at its most striking in a piano/percussion statement-response passage. Consolation contains a melody line in the piano doubled by a keyed percussion instrument I couldn’t identify, but the piece’s surrounding preamble and coda come from a different world than the Liszt pieces referred to in the title.

Tristram Williams gives an invigorating interpretation of the Etude for Trumpet in C. The composer plays rhythmic games non-stop in this brightly-textured piece that begins as a piano toccata escorting a jumpy brass line. As in the preceding duets, the keyboard doesn’t take a back seat but insists on equal status, and equal work-load. At 3:40, Williams employs a mute so that the heat fades somewhat, even if the impetus is not slowed, the combined output remaining spiky. Of course, the mute comes out for the last brisk minute and the collaboration – a taxing one with its metrical complexities – comes to an abrupt end.

City of Snakes – using B flat bass clarinet, piano, bass and drums – refers to Hobart, Harvey’s home town and apparently a city subject to reptile infestations in bush-fire season. This brings into play Ashley William Smith, who impressed me mightily with his ANAM account some years ago of the Lindberg Clarinet Concerto. The final piece on this CD is a vehicle for Smith’s instrument which occupies the sonic forefront. In its very accessible be-bop rush, Ughetti takes the floor for a substantial solo break and Harvey keeps himself busy. The bass player remains unidentified and his/her actual sound is an inconclusive one – is it electric, natural, or over-miked? Whatever, the work’s effect is optimistic, summoning up memories of 1960s Melbourne jazz club fare, if more exciting in its bravado than much that you heard live in that decade.

Harvey as a performer is full-frontal, unapologetic, master of a rolling sonority even when the music is emotionally recessive. This exhibition of his compositions shows how complementary the acts of creation and performance are for him. While the shorter duets and concluding quartet hold your attention for the craft exerted in their combinations and alterations of sonorities, I think that the half-hour sonata gives the listener a bitingly clear picture of the remarkable musician’s intellectual and – for want of a better word – spiritual attributes. As a study of the composer/pianist at work, this Sonata No. 2 gives us unmistakable essential Harvey.