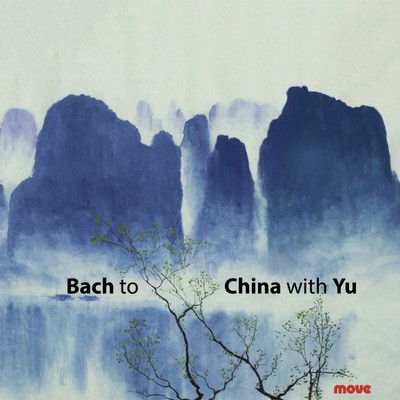

BACH TO CHINA WITH YU

Julian Yu

Move Records MD 3474

Much of this latest volume of works by Julian Yu involves clarinet, violin and cello. In fact, Robert Schubert‘s clarinet features in each of the four varied elements on the CD, as it has on two previous Move Records publications that present the composer’s chamber music involving that instrument. Also appearing here are pianist Akemi Schubert, violinist Yi Wang, and two well-known cellists in Virginia Kable and Josephine Vains.

Now, to content. The album starts and ends with Bach, whose music enfolds Yu’s arrangements of 24 Chinese Folksongs (some of which also contain Bach snippets) and two tracks of Dances from the XII Muqam, a collection of traditional Uyghur melodies. As anticipated, the longest of these four compositions is the assemblage of folksongs, but Yu fans will have heard these some years ago – 2019, to be exact – when pianist Ke Lin recorded the composer’s 50 Chinese Folk Songs. As far as I can see, Yu has revisited 22 of his original 50 and transcribed them for Schubert, Yi and Vains; the two odd-persons-out are Su Wu Tends the Sheep and Wild Lily.

As I said, there’s some Bach included in the folksongs as Yu elects to employ some of this composer’s bass-lines (and those from other composers) as supporting material for his collated melodies. Some of these interpolations are easy to find; others escaped identification by this willing listener.

Beginning with a solid slab of Western music, Yu has arranged the Chaconne in D minor from the Violin Partita BWV 1004, written sometime between 1717 and 1720. He’s not alone in this exercise and admits to drawing on transcriptions by Mendelssohn (who wrote a piano accompaniment for the piece), Schumann (who did the same), Busoni and Raff (who both did simple piano transcriptions, although the latter also made a version for full Romantic orchestra), and Brahms (a splendid version for piano left-hand). In this performance, we hear Schubert, and the string partnership of Yi and Kable for the only time on this CD.

As for the ending, we hear the organ Passacaglia in C minor for organ BWV 582 from sometime between 1706 and 1713. Yu gives us the famous bass line on the cello but has dilated the first note of each bar to a dotted minim, so the time-signature changes from 3/4 to 4/4. On top, the composer introduces scraps from arias and instrumental interludes heard at the Peking Opera; some are original, some Yu-composed. In all, we hear about twelve variations – down on Bach’s twenty – and the results prove to be disarmingly deft.

But you could say that about the whole set of 28 tracks. The arrangements are clever in conceit and clear in texture, if only rarely arresting. As you’d anticipate, the most challenging work comes first with the Chaconne. Yu begins in orthodox fashion with clarinet and cello outlining the eight bars of basic material before the piano enters discreetly with some melodic and harmonic reinforcement. All three are in operation with few signs of disturbance until we reach bar 25 where Schubert takes the melody line and elaborates it into a semiquaver pattern while clarinet and piano take on the chordal punctuation.

From here on, the central melody is shared between all three players while the re-composer begins to add flourishes, distinctly new lines, all the while indulging in some neatly dovetailing klangfarbenmelodie. We come to a slower oasis at bar 77 when the clarinet takes over from the semiquaver-addressing piano, giving us a calmer ambience which lasts up to the arpeggio direction of bar 89 which the piano takes on board and follows with a general attention to the written notes, apart from a few deviations, the whole fraught sequence winding up with a powerful bass line of striding quavers from cello and piano which is not in the score but makes a remarkably Brahmsian lead-in to the D Major reprieve at bar 133.

This is taken at a slow pavane speed and Yu recycles the opening variation of this segment as a subordinate component while gradually building up intensity with the piano adding more arpeggiated ferment, until the reversion to the minor key, at which point the piano disappears and clarinet and cello play the first two variations from this point by themselves, a few triple-stops from the original falling by the wayside. The piano gets an attack of the triplets well before they should turn up in bar 241 but by this stage we’ve been treated to so much linear displacement that the prepositioning hardly raises any eyebrows.

And so to the final peroration which is given with more late Romantic magniloquence in the best Busoni tradition. Also in something of an arranger’s tradition, Yu fleshes out that final noble single D with a full chord. So do Schumann, Mendelssohn, Raff and Busoni (who indulges himself with a tierce). The solitary exception is Brahms, who consents himself with three massive octave Ds – a man who knew when to leave well enough alone.

I heard the folksong Su Wu Tends the Sheep with more interest than most because it concerns a real person: a 2nd-to-1st BC diplomat who was detained on a mission for 19 years and put to menial work while under what amounted to imprisonment. The melody is here given mainly to the violin, the clarinet a late entry to the mix. But the message is clearly one of longing (for the homeland?) even in the middle of pastoral solitude – or so I feel about what is a warm, even sentimental lyric.

The other novelty in this collection is Wild Lily from the Shanxi province. A simple melody in four phrases, Yu sets it simply enough for violin with clarinet discordant underpinning, then again where the clarinet bears the melody while the cello accompanies in an atonal language – nothing too savage in either half, only single notes but deliberately at odds with the tune’s simplicity.

As for the other 22 elements in this collection, I refer you to my review of Ke Lin’s Move Records performances of the 50 Chinese Folksongs back in 2019. I believe I commented on all of the others treated here and have nothing new to add apart from predictable remarks about the new settings’ timbres. The same problems still apply: the arrangements are brief (eight of them are under a minute long, including Wild Lily) and, after a while, they fuse, so that it’s hard to distinguish between something as well-known as Jasmine (thanks to Puccini’s Turandot) and Willows Are New.

Fusing his Chinese melodies with the West, Yu uses a Handel bass to underpin the Mongolian melody Gada Mailin, then a Bach quotation from the B minor Mass in Picking Flowers. A more original device comes in Little Cabbage from the Hebei province where the cello picks out the vegetable’s name notes for underpinning; this probably works well because of the resultant motif’s pentatonic nature. More difficult to discern was the quotation from Brahms’ Symphony No. 4 during Lan Huahua, although Yu made it easier for us by opening A Rainy Day with the first eight bars to this symphony’s Passacaglia.

It’s back to the B minor Mass for the Sichuan tune Jagged Mountain, clarinet and cello presenting it in turn even if it tended to throw the melody into the background. An outburst of familiarity came with the Shaanxi air A Pair of Ducks and a Pair of Geese which enjoyed the bass-line on which Pachelbel constructed his mellifluous Canon in D, beloved of wedding-organizers. Also easy to pick up was the use of the left-hand to the Goldberg Variations‘ opening statement during Taihang Mountains.

But we encountered more difficulties with Willows Are New, during which Yu employed some famous Bach motifs that went straight past this bat into a no-doubt-contemptuous keeper’s gloves. But I recognized at least one of the Brahms Symphony No. 1 bursts that supported the medley of three Shanxi and Shaanxi folksongs and that was the chorale spray that climaxes the finale at bar 407. However, the impact of the German master’s rich chromaticism made the track surprisingly Western/European, a factor that also struck me in the last of the collection, Thunder a Thousand Miles Away, which seemed to be a mix of three-part invention and (limited) fantasia.

But so what? Yu’s compositional career has been informed by his homeland and further education here; the least you’d expect is a happy relationship between the two ‘schools’, as we find on this disc. Still, he strikes the same problem as most other writers when dealing with the material for his Three Dances from the Uyghur people of Xinjiang: the tunes are finite and the changes you can ring on them present challenges beyond simple repetition in new timbres. The first dance is extensive, showing a good deal of inventiveness in edging the basic material in several directions, made all the more difficult by the number of repeated notes involved, especially in the piece’s middle pages.

More surprising was the character of the melody which seemed to share characteristics with the folk music from various countries as collected by Bartok and Kodaly than with the 24 folksongs sitting alongside it on this CD. Yu grouped his second and third dances together; well, sort of: the tempo increases for the third which concludes in an almost Rossinian galop. Oddly enough, only in these dances did you come across faint cracks in the trio’s ensemble work, mainly due to slight hesitations about entries and the delivery of some pretty simple syncopations.

For organists, Bach’s big Passacaglia and Fugue are impregnable musical fortresses. You can’t really take exception to Yu’s employment of its bass progression for his own composition, but he is operating with a melodic and harmonic pair of palettes that are very limited when compared to the original. That said, you can take pleasure in Yu’s interweaving upper voices, particularly if you can keep out of your mind the monumental welter that straddles your consciousness from bar 144 to the end of the great organ construct. And, as the poet says, a man’s reach should exceed his grasp and this CD is witness to Yu’s high level of ambition.