Thursday September 1

Wood, Metal & Vibrating Air

Tamara Smolyar

Robert Blackwood Hall, Monash University at 7:30 pm

This has been an ongoing cycle featuring several well-known pianists performing under the heading ‘The piano – up close and personal’. Which is apparently what it says; while the performances are held in the large Blackwood Hall, the audience is grouped on-stage around the soloist – so far, the participants have included Caroline Almonte, Stefan Cassomenos, Andrea Keller, Simon Tedeschi, Lisa Moore. Tamara Smolyar is last in this series of recitals. She is performing a new work by her colleague in Monash University’s Music Faculty, Kenji Fujimura, the Australian premiere of Anatoly Documentov’s Mood 2: Preludes, another world premiere in Livia Teodorescu-Ciocanea’s Briseis, yet another first hearing in Anthony Halliday’s Introduction and Fugue for Tamara, Jane Hammond’s There is a solitude enjoying its first outing, and an arrangement for duo pianists by Halliday and Smolyar of Rachmaninov’s Trio Elegiaque in D minor. A night packed with novelty and exploration.

Thursday September 1

Hrusa Conducts Suk’s Asrael Symphony

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Hamer Hall at 8 pm

This is a huge gamble; as far as I can see, solely based on the attraction of having conductor Jakob Hrusa direct another big tract of Czech music, if not as varied in content as his complete Ma Vlast with the MSO in 2014. The long symphony that Suk wrote in memory of Dvorak, his father-in-law, then reformed from a celebration to something darker when his wife died the following year, is a complete unknown to me. Hrusa took it to the London Proms two years ago and the work has enjoyed the attention of several enthusiastic promoters in Britain. Tonight, it is allied with Mozart’s Symphony No. 25 in G minor – the one that enjoyed a lot of exposure (well, its opening bars did) in the film Amadeus.

The program will be repeated on Friday September 2 in Robert Blackwood Hall, Monash University at 8 pm.

Friday September 3

Elision

Australian National Academy of Music at 7 pm

I’ve been an Elision follower for many years – that is, before the group shifted base and went international. Still, admiration has to be kept within bounds and this night’s trick speaks of a superhuman talent to be in two places at once. According to the ANAM calendar of events, the group is collaborating with musicians from ANAM at the South Melbourne Town Hall in German composer Enno Poppe’s (apparently) challenging Speicher – which could mean granary, an attic storage room, or computer memory. Whatever the case, the players are also down to perform the work in the Capital Theatre, Bendigo as part of that city’s Festival of Exploratory Music. Look, they could be doing both: the South Melbourne performance is at 7 pm, Bendigo’s is scheduled for 9 pm. But then, the work lasts about 75 minutes so it would be close-run thing that would involve the sort of driving that shouldn’t be encouraged on the Calder. Or perhaps the participants will be split in half. Either way, you’d want to check exactly what’s going on before the date.

Saturday September 3

Three Twentieth-Century Masterpieces

Ensemble Gombert

Xavier College, Kew at 5:30 pm

And they are Vaughan Williams’ Mass in G minor and two scores unknown to me: Hugo Distler’s Totentanz and Petr Eben’s Horka hlina. The German composer is a celebrated force in his country’s choral tradition and, in his comparatively short life, he wrote a great deal of music for choirs. This Dance of Death has many sections, some of them spoken. Bitter Earth, Eben’s cantata, requires a baritone solo, choir and piano. As for whether these are masterpieces, the proof is yet to come, although you can be sure that the Gomberts will give each work their best efforts. Let’s hope they’re persuasive.

Sunday September 4

Leonskaja Mozart

Australian Chamber Orchestra

Hamer Hall at 2:30 pm

Hard to tell who takes pride of place at this event – the Soviet/Austrian pianist or the plain Austrian composer. Both have a hand in the central work, the Jeunehomme Concerto in E flat: the only one you hear regularly of the first 13 or 14 in the catalogue. On either side is a string work: the lavishly opulent Sextet from Strauss’s Capriccio, and Beethoven’s E flat Major Quartet, the later Op. 127 one, arranged for string orchestra by . . . well, it could be the absent Richard Tognetti, but there are plenty of other takers. Leonskaja, by the way, is not taking on leader duties; these are the responsibility of Roman Simovic, one of the two London Symphony Orchestra concertmasters, who is guest director.

The program is repeated in Hamer Hall on Monday September 5 at 7: 30 pm.

Sunday September 4

Classical Romanticism

Trio Anima Mundi

Holy Trinity Anglican Church, East Melbourne at 3 pm.

Second in the ensemble’s subscription series, this begins and ends with works by two friends. Sterndale Bennett’s Chamber Trio in A, an early work, has three movements only and is not over-taxing but will make an intriguing contrast with the last piece on the program by his cobber Mendelssohn: the ubiquitous Piano Trio in D minor. In between come two small-scale bagatelles by Theodore Dubois, whose name is known to me solely as an organ composer. But here is his Canon for piano trio, two pages in which the imitative work is confined to the string instruments at the 2nd. Dubois’ Promenade sentimentale in A flat is more substantial but really a show-case for violin and cello with the keyboard doing arpeggio support duty for most of the time. The group’s move to East Melbourne took me by surprise; intending to attend the first recital this year, I drove round for some time without finding a parking space free that accommodates you for more than an hour. I’d suggest taking the tram, or adventuring on the train to Jolimont.

Wednesday September 7

Beethoven Festival – Piano Concerto No. 1

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Hamer Hall at 7 pm

Paul Lewis will be soloist in this celebration of the complete piano concertos. Conducting is Douglas Boyd, whose complete Beethoven symphonies cycle at the Town Hall five years ago was a remarkable success. It’s quite a challenge, this C Major score, gifted with a chirpy finale but preceded by two substantial essays that test a pianist’s capacity for variety of touch, as well as the power to sustain some lengthy paragraphs. As preludes come Haydn’s Symphony No.102, contemporary with the evening’s concerto, and Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony No. 1 – no, I don’t understand how this fits in, either. You’d presume that the MSO will play the composer’s orchestral arrangement of 1935 rather than the original format for 15 instrumentalists. But it still makes a challenging aural experience, even 110 years after its production.

Saturday September 10

Sato and the Romantics

Australian Brandenburg Orchestra

Melbourne Recital Centre at 7 pm

A guest new to me – and the Brandenburgers, I think – Shunske Sato is an American-based Baroque violinist. Which makes it all the more interesting that he is playing the Paganini Concerto No. 4, although he has recorded all of the Caprices on a period instrument. Still, there’s nothing like upping the ante and handicapping yourself even further than just handling the technical demands; throwing in gut strings will make a big difference to Sato’s ease of negotiation Also to be heard is Grieg’s Holberg Suite – the poet lived in the Baroque era but this music is just as unusual fare for this orchestra as is the concerto – and Mendelssohn’s String Symphony No. 2 in D: 10 minutes’ worth of early adolescent skilfulness but not much there to sink your teeth into. There must be more on the program but I can’t find out what; perhaps we’re in for an early mark.

This program will be repeated on Monday September 11 at 5 pm.

Saturday September 10

Beethoven Festival – Piano Concertos Nos. 2 & 3

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Hamer Hall at 7 pm

Back with Paul Lewis as soloist in the only occasion during this festival where you hear two concertos. The C minor work is well-known but you have to wait quite a few years before you come across the B flat (originally, the first composed of the lot). It’s a fair test of the pianist as the two works couldn’t be more temperamentally opposed. For reasons that defy any sort of logic, the concertos are separated by Webern’s Five Movements for String Orchestra, which I assume is an arrangement of the well-travelled Five Movements for String Quartet, Op. 5. They’ll do good service as a complete change of pace but, in this context, it’s hard to see the point. Maybe it will all come clear on the night; or maybe it will just remain an inexplicable programming anomaly.

Monday September 12

Rare Gems

Quartz

Melbourne Recital Centre at 6 pm

The gems begin with Fanny Mendelssohn, Felix’s well-beloved sister. Her String Quartet in E flat has only been extant for a little over 25 years and, alongside the composer’s multiple songs and piano pieces, is a true rarity. Frank Bridge’s Three Idylls are forever associated with the composer’s student, Benjamin Britten, who rifled the middle one for his striking Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, but the idylls themselves make for genially astringent listening experiences. Ervin Schulhoff died in the Wulzburg concentration camp but his first string quartet has gained more performances than most of his music, if CD recordings are any indication. But Quartz has it right by classifying this score as rare; whether it’s a gem remains to be seen.

Wednesday September 14

Beethoven Festival – Piano Concerto No. 4

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Hamer Hall at 7 pm

Lewis takes on the most languid and contemplative of the five concertos. Haydn’s Drumroll Symphony No. 103 sets the night’s tone – somehow. The two works are separated by about a decade in terms of composition. And the finale is Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night, that romantic effusion for strings that comes to one of Western music’s most luminous conclusions in a wash of harmonics. The program sort of balances the first one in this series, so, along with Boyd’s trustworthy interpretation and Lewis’ facility, we should be grateful to hear works by two composers who are often strangers to live performance – and I don’t mean Beethoven.

Thursday September 15

Beyond all this . . .

Israel Camerata Jerusalem Orchestra

Melbourne Recital Centre at 7:30 pm

Founded in 1983, this ensemble is fortunate enough to have retained its original director and conductor – Avner Biron. Tonight, the ICJO makes its Australian debut with guest Zvi Plesser, whom I last heard in this venue nearly seven years ago collaborating with the Jerusalem Quartet (see directly below). The Camerata and soloist are rolling out the big guns with Dvorak’s Cello Concerto, a lengthy piece that never gets stale. To keep it company comes Haydn’s Symphony No. 85, La Reine – so-called because Marie Antoinette liked it; not exactly a ringing guarantee of quality but the symphony survives with flying colours. And also flying, the nationalistic banner is hoisted by way of the respected Ukrainian/Israeli composer Mark Kopytman’s earnest and spikily-scored work that gives this night its title.

The orchestra plays again on Monday September 19. Kopytman puts in another appearance, with another of his works that the ICJO has recorded: Kaddish, which can have either a viola or cello soloist; obviously, on this night, Plesser will do the honours. He also fronts the popular Haydn Concerto in C. Book-ending these are Bartok’s Divertimento for strings and the feather-light Symphony No. 5 by Schubert.

Saturday September 17

Jerusalem Quartet

Melbourne Recital Centre at 7 pm

Appearing for Music Viva, as usual, this well-known group is offering two programs, both containing a piece of Australian craft: the String Quartet No. 3, Summer Dances, by Ross Edwards. In five movements, this work is four years old and I think it must have been played here at some stage; if so, the memory has not lingered. Tonight, the surrounding elements are Beethoven in B flat – the last of the Op. 16 set – and Dvorak No. 13, reflecting the composer’s delight at being out of the United States and back home. In all, it’s a happy-tempered night’s work

The Jerusalem musicians will return for a second program on Tuesday September 27. With the Ross Edwards, they will play the first Razumovsky of Beethoven and Haydn’s Lark, Op. 64, No. 5. Again, this promises contentment rather than musical angst.

Saturday September 17

Beethoven Festival – Piano Concerto No. 5

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Hamer Hall at 7 pm

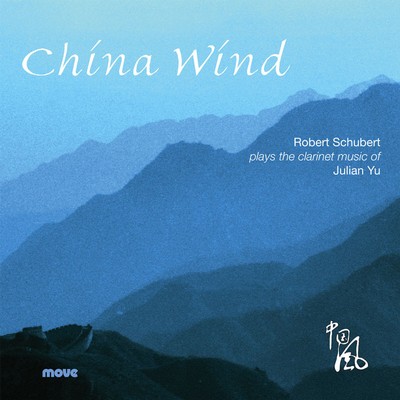

The festival ends with Paul Lewis mounting an assault on the Emperor: an always majestically confronting experience with a circuitous first movement that has momentarily befuddled several pianists in live performance over the years. Completing a Haydn trifecta, the MSO under Douglas Boyd plays the Symphony No. 104, the London and last of the composer’s mighty output in this form. As for the de rigueur Second Viennese School offering at these events, tonight it’s the turn of Alban Berg; nothing so simple as the Three Orchestral Pieces but a transcription for orchestra by Julian Yu of the defenceless Piano Sonata. Yes, some of us are grateful that Schoenberg and his close colleagues/students have not been completely forgotten but how they fit in with Haydn and Beethoven in any terms but national – and that’s a doubtful quantity – is one of the year’s programming mysteries

Sunday September 18

Tricolore: Three Italian Maestri

The Melbourne Musicians

St. John’s Southgate at 3 pm

Back in their usual habitat after an excursion to MLC for a Beethoven+Mozart feast in July, the Musicians take on three well-known Italian scores. Two similar works are Albinoni’s Oboe Concerto – well, one of the eight; probably the D minor from Op. 9 – and Marcello’s Oboe Concerto, also in D minor. Both will feature Musicians’ regular Anne Gilby as soloist. Completing the trio of offerings is Pergolesi’s Stabat mater with soprano Tania de Jong and counter-tenor Hamish Gould. The organization has enjoyed success with this work in previous years, although my experience of it has usually involved two female voices – which is a pretty good indication of how little I get around. Still, the components make for a congenial afternoon’s listening with nothing too tension-inducing, except for the soloists.

Tuesday September 20

The Wanderer

Seraphim Trio

Melbourne Recital Centre at 7 pm

Now here’s a night for Schubert enthusiasts. The Seraphims – violin Helen Ayres, cello Timothy Nankervis, piano Anna Goldsworthy – will play both the trios in one sitting. Actually, there’ll be an interval, so it’s a double sitting. Not an impossible undertaking but it is an ordeal to test the players’ concentration. No, they won’t have trouble with the notes but there are some big canvases in these eight movements and maintaining your focus throughout can be daunting. That’s the joy and terror of chamber music: there’s no place to hide, least of all in the MRC’s Salon. The trio members have been buoyed by audience responses to their Beethoven trios cycle last year – hence this year’s move to his admirer-from-afar. The title has me puzzled, though. Is it the song? A reference to Schubert’s love of hiking? Or does it pertain to his amiable meandering round the key spectrum? Let’s hope the game is worth the candle and the interpretations can improve on those thrown up by outfits like the Beaux Arts.

Wednesday September 21

Shakespeare in Love

Songmakers Australia

Melbourne Recital Centre at 6 pm

This offers a vast range of repertoire, everything from Schumann (Der Dichter spricht? A piano solo?), Berlioz mourning the death of Ophelia in Legouve’s take on Gertrude’s description of the tragedy, Brahms giving actual voice to Ophelia, through Korngold and Grainger’s melancholy voicing of Desdemona’s song, some side-tracks to the poet’s fellow-countrymen Quilter and Finzi, a sonnet setting by Kabalevsky as a side-dish, and Australian Alison Bauld’s vision of somnambulistic Lady Macbeth doing the rampart rounds. Andrea Katz will accompany Songmakers regulars soprano Merlyn Quaife, mezzo Sally-Anne Russell and bass-baritone Nicholas Dinopoulos. A pretty well-focused hour’s entertainment delivered by reliable musicians.

Wednesday September 21

Basically Beethoven #3

Selby & Friends

Deakin Edge, Federation Square at 7:30 pm

Not just basic: nothing but Beethoven here. The night opens and closes with piano trios, as expected: Op. 1 No. 2 in G Major, while the Ghost in D Major brings up the rear. Kathryn Selby’s guests tonight are the top and bottom ends of the Goldner Quartet: violinist Dene Olding putting in a rare Melbourne appearance, and cellist Julian Smiles who is participating also in the last of this subscription series on November 8. Olding will also perform the Sonata No. 8 in G, while Smiles plays the first of the Op. 102 in C Major, a sternly compressed two-movement structure that in parts has the same emotional breadth as the last piano sonatas. Selby and her associates invariably produce interpretations of remarkable depth and control, object-lessons for any aspiring chamber music tyro and for devotees of the craft.

Friday September 23

Sara Macliver, Paul Wright & The Italian Baroque

ANAM Orchestra

Australian National Academy of Music at 7 pm

A program that could have been filched wholesale from the Australian Brandenburg Orchestra. Considering its contents, it suddenly struck me how little Baroque music I’ve heard the Academy musicians play; well, they’re making up for it tonight. Soprano Sara Macliver sings Caldara’s slow-stepping In lagrime stemprato from the oratorio Magdalene at the feet of Christ, and later Perseus’s aria Sovente il sole from Vivaldi’s serenata Andromeda liberata with the night’s director, Paul Wright, supplying the violin obbligato line. In fact, Vivaldi scores well here with the Il Riposo Violin Concerto, a Christmas celebration, the La Folia variations, and the Sinfonia in D for strings RV 125. Starting the night is Boccherini’s Night Music of the Streets of Madrid with its clever guitar imitations and atmospheric crescendo and diminuendo effects; Gregori’s Concerto Grosso No. 1 in C from the Opus 2 set follows. Later on, we are treated to an arrangement by Joe Chindamo of a Scarlatti Sonata in G Major – which admits of a pretty large field of possibilities.

Monday September 26

Intimate Beethoven

Australian Chamber Orchestra

Melbourne Recital Centre at 7:30 pm

The ACO comes to town out of its subscription series; well, part of it is coming. This program comprises two works only: Mozart’s String Quintet in G minor, and Beethoven’s String Quartet in A minor. The personnel are all core ACO personnel: violins Helena Rathbone and Linda Palladini, violas Alexandru-Mihai Bota and Nicole Divall, and cello Timo-Veikko Valve who is the ensemble member of whom we have seen most in a chamber music role at Selby & Friends recitals. As for the music they have prepared, Mozart doesn’t come much more sombre than this quintet which, oddly enough, has a happy ending tacked on, presumably to nullify the minor-tonality gravity that overpowers much of the score. As for the Beethoven, this is the five-movement work with a long central Hymn of Thanksgiving which often sounds like anything but. It’s great to see that the players are not fobbing us off with mere entertainment but are heading straight for the tragic heartland of both composers.

Thursday September 29

The Offering

Flinders Quartet

Melbourne Recital Centre at 7 pm

Guest with the popular quartet will be pianist Benjamin Martin who will assist in winding up the program with the Brahms Piano Quintet in F minor, puzzlingly listed as Op. 34a which I assume is meant to differentiate this original scoring from the Op 34b arrangement for two pianos. Martin will also take part in the world premiere of Elena Kats-Chernin’s Piano Quintet No. 1 which gives the evening its title. The Flinders players are themselves performing another world premiere: Stuart Greenbaum’s String Quartet No. 7 with the cummings-style name 4 before (and after) 5. To flesh out the night, the quartet will also essay Shostakovich No. 5, the first one with the movements joined by attacca directions. Plenty of novelty here alongside two superb repertoire staples.

Friday September 30

Four Saints in Three Acts

Victorian Opera

Merlyn Theatre, Coopers Malthouse at 7:30 pm

An opera by Virgil Thomson with a libretto by Gertrude Stein, this work has fascinated many musicians for years. For some, its delights are wrapped in a deliberate maze of oblique suggestions and intentional obscurities but, to get the best out of it, you probably have to adopt an old-fashioned abnegation of rationality and run with whatever happens. The cast is drawn from the company’s Youth Opera personnel; the pit will be peopled by the organization’s Youth Orchestra conducted by Fabian Russell. Director is Nancy Black and the production will involve 3D imagery, as we have experienced with the company’s previous The Flying Dutchman performances at St. Kilda’s Palais. St. Ignatius Loyola, two St. Theresas of Avila and a panoply of other canonized characters sing whatever action there is and, at the end, the company is hosting a (separately ticketed) dinner inspired by Alice B. Toklas’ notebook, at which the hosts will be soprano Merlyn Quaife as Toklas herself and Robyn Archer will appear as Gertrude Stein. Hath earth anything to show more fair?

A further performance of this work will be given on Saturday October 1 at 7:30 pm.

Friday September 30

Respighi’s Fountains of Rome

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Hamer Hall at 8 pm

A travelogue to satisfy any devotee of the once-Eternal City, the MSO performs Respighi’s Fountains of Rome (an all-day tour involving the Valle Giulia, the Triton, the Trevi and the Villa Medici) and then the Pines of Rome (at the Villa Borghese, near a catacomb, up the Janiculum, along the Appian Way). In sequence, the works present an orgy of orchestration, the effects brilliantly conceived and irresistible. Guest pianist Nelson Freire, one of Brazil’s finest musicians, takes the solo part in Schumann’s modestly flamboyant Piano Concerto, and Brazilian-born conductor Marcelo Lehninger, who toured South America with Freire eight years ago, begins the event with the Concert Overture in E Major by Szymanowski – an early work that matches the lushness of the Respighi extravaganzas at night’s end.

This program will be repeated on Saturday October 1 at 2 pm, and on Monday October 3 at 6:30 pm.