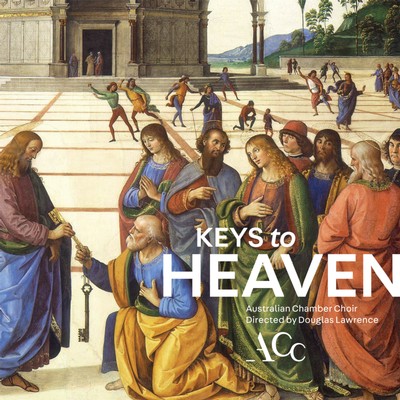

KEYS TO HEAVEN

Australian Chamber Choir

Move Records MCD 659

A reconstruction is the main point of interest in this new CD from the Australian Chamber Choir of Melbourne (similar to the Australian Chamber Orchestra of Sydney). Elizabeth Anderson, long-time ACC member and wife of the body’s artistic director/conductor, came across a fragment or six written by Agata della Pieta, one of that fortunate group educated at the Ospedale in Venice with which charitable institution Vivaldi’s name remains inextricably linked. Anderson discovered some parts for Agata’s setting of Ecce nunc (or Psalm 134) in Venice’s Benedetto Marcello Library and built up a working version for public presentation.

As well as this novelty, the choir has produced another reading of Palestrina’s Missa Aeterna Christi munera to sit alongside its previous recording of 2014/15. Among a scattering of bibs and bobs, Allegri’s Miserere enjoys an airing; I think I first heard the ensemble sing this polychoral warhorse in 2010. More Allegri comes with Christus resurgens ex mortuis for 8 voices. And there’s a neatly wound version of Palestrina’s papal office-affirming Tu es Petrus for six voices, director Douglas Lawrence making sure we hear the Secunda pars which is omitted in many recordings and scores.

The CD itself is a compendium with the Christus resurgens and Palestrina mass coming from a live performance in Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church, Middle Park, Melbourne given during November 2019. The latter composer’s motet also emerges live from a week before in St. Andrew’s Church, Brighton, Melbourne. The all-too-well-known Miserere setting seems to be a collation of two performances: one at the Middle Park church on August 23, 2023, the other three days later at Mandeville Hall in Toorak, Melbourne.

As for the Agata psalm-setting, the greater part of this recording took place in the Scots’ Church, Melbourne on May 4 2022, eleven days after the work’s world premiere in Terang, Victoria. One solitary track from the ‘new’ score – the contralto aria In noctibus – was taped at the Collins Street venue almost two years later on April 12, 2024. Which makes this last the most recent track on a disc which has enjoyed a five-year gestation.

Anderson’s realization divides the psalm into four sections. The first sentence is covered by two movements: a soprano solo with choral interference, then a plain soprano solo. Unfortunately, the booklet accompanying this disc allots to the aria a line of text that is actually included in the soprano-plus-chorus opener, which led to an inordinate amount of repeating the tracks to trace what was going on. The specially-recorded contralto solo takes care of the second sentence, and the third and final one is given to the chorus. Fleshing out this brevity, we hear a doxology in two parts, the initial Triune extolment given to two solo sopranos, the following unlimited-time guarantee fulfilled by a single soprano and chorus – just as at the work’s opening which provides its material.

Lawrence employs modest forces to bring this score to life, including a string quintet and Rhys Boak on organ. His choral forces are also modest with six sopranos and four each of altos, tenors and basses. Still, the work itself is hardly Baroque-Heavy, as you can predict from its opening ritornello: a mobile, gentle chain of semiquavers, delivered carefully if marginally out-of-tune at the end of bar 3: a predictable problem when playing non-vibrato in stile antico. Amelia Jones‘ soprano makes a clean business of the opening solo and the choral body continues the placid ambience established at the opening.

The following aria for Jones with Jennifer Kirsner‘s obbligato violin, Qui statis in domo Domini, presents an adroit duet contemporaneous with many another more complicated (and more interesting) exercise in this form to be found in Bach’s cantatas and Passions. Reconstructor-contralto Anderson also enjoys Kirsner’s assistance through her aria which shows that the singer’s voice has remained the same over the many years that I’ve been listening to it it; accurate, but awkward in delivery.

The Benedicat te chorus is brief, standing in as a palate-cleanser, just like a chorale in the more substantial German works being written at the same time as Agata was composing this gentle piece. A soprano duet – Jones and Kristina Lang – begins the doxology, distinguished by the excellent complementary timbre of the singers and the occasionally scrappy upper violin contributions in triplets. Then Jones enjoys a solo – shorter than in the opening movement – for the Sicut erat up to et semper, before the choir enters to re-appraise all the concluding lines of this placid wind-up to so many prayers in the Western Christian tradition.

As a whole, the newly-discovered setting gives us an eminently approachable sample of this period’s compositional style, Agata’s instance notable for its benign atmosphere and generally predictable progress. We’re introduced to a creative voice that few of us would encounter across our life-spans, and one that speaks with a sort of quiet confidence. How much is Agata and how much Anderson, we’ll probably never know, but the composite entity makes for attractive listening, excellent material for any chamber choir who wants to engage with a score that is gracious, elegant and reverent – not descriptors that you can apply to much that came out of the magniloquent city of St. Mark.

Palestrina’s motet enjoyed a straightforward interpretation; a bit four-square for my taste, sticking to its pulse with few signs of relaxation (except at the cadences to both parts). But the output remained dynamically balanced across all six lines and the not-too-long melodic arches came across as shapely, except for a length abridgement at the end of the first super terram where sopranos (canti), altos and tenors bounced off the final syllable in order to maintain the rigid tempo. But I suppose when you’re dealing with rocks, the inclination to present an inexorable surface is very tempting.

I’m assuming that there was something of a carry-over of personnel between the mass tapings across the 4/5 year gap; certainly I recognize a few names in this current CD list that were part of the ensemble when I was reviewing the ACC’s Middle Park events. Nothing else I’ve heard has come close to the 1959 recording of this work by the Renaissance Singers in the Church of St. Philip Neri, Arundel: the most riveting, ardent interpretation you could wish for. You’re in for a more balanced demonstration of Renaissance choral music in Lawrence’s hands. Here, tout n’est qu’ordre et beaute, sort of, but you can forget about the luxe and volupte even if calme is all the go.

The ACC’s Kyrie is a model of linear clarity and parity of parts; no change of pace for the Christe but a steady and regular field of play with almost the same disposition of singers as for the Ecce nunc, an extra bass giving substance to that gloriously singable line. More regularity emerged in the Gloria, resulting in a curtailed second syllable in the first Patris just before the Qui tollis chords. However, the ensemble made a fine fist of the piece as a complete construct and – marvel of marvel for us old-time Catholics – you could decipher every word.

A few details intrigued during the progress of the Credo, like the delicate breaks in the Genitum non factum statement up to facta sunt; also a softening of dynamic without the usual deceleration at the Et incarnatus moment; as well, a brightening of attack at the Et in Spiritum Sanctum affirmation; and the realization of those warm key changes at simul adoratur and Et expecto resurrectionem. Despite the rhythmic inevitability (to this geriatric mind, reminiscent of the Creed in Schubert’s G Major D. 167), the luminous pairing of lines that punctuate this movement sounded finely etched and even the two passages of rather ordinary counterpoint impressed for their transparency.

If you were going to exercise rhythmic fluidity, you’d have to engage in it during the Sanctus, where the Hosanna is ideally staged for drama and a suggestion of haste. Not here; Lawrence keeps his singers bound to an unvarying speed. Not even the Benedictus trio shows any deviation from the regular, although the Hosanna return manages to engender a restrained elation. You can actually sympathize with the conductor’s approach to this composition where the chaste sparseness of its content makes a clear parallel with the abstract eloquence of plainchant.

For the Agnus Dei, the pace is slower, more considered as the composer indulges in plenty of textual repetition (as compared with the speedy despatch of the Gloria and Credo). Again, the balance is very fine, each line distinct in the mesh. But the work’s glory is the expansion into five parts for the final pages. This splits the tenors in two and the ACC singers sound appreciably thinner. Still, they are distinguishable in this reading and refrain from braying their top notes but maintain a quiet and controlled output in sync with their colleagues.

There are very few pages in all Western music that offer the consolations of Palestrina’s concluding bars from the dona nobis pacem emergence to the end. When I’ve sung this in previous incarnations, the pace has generally slowed, possibly because of the nature of these final pleas. Very little compares with the subtle consolatory suggestions of those flattened leading notes in the tenor and bass lines as they approach that breathtaking, concluding plagal cadence, here articulated with cautious devotion.

There’s not much to say about the choir’s version of Allegri’s Miserere. Lawrence has rehearsed his men effectively so that the plainchant sections impress for their gravity and sense of space; just as in the best monasteries, there’s all the time in the world. The five-part choir shows itself willing to give power and impetus to their work while the solo quartet – sopranos Elspeth Bawden and Kate McBride, alto Anderson, bass Thomas Drent – operate comfortably in their remote, exposed roles. I don’t know which of these sopranos takes the high Cs but the pitching is exact, the ornamentation pretty lucid.

But the number of participants involved is only 18, which cuts down to 14 for the five-part body when you deduct the four soloists. More impressive is the solid output of the 21-strong group that presents the Christ resurgens motet. There’s plenty of power at the extremities with 7 sopranos and 6 basses surrounding quartets of altos and tenors. The sound is sumptuous throughout, with a nice difference in character between the two choirs at antiphonal passages, the full-bodied stretches a splendid affirmation, particularly during the powerful Alleluias that conclude the three Epistle to the Romans extracts which make up the elements of this polyphonic gem.